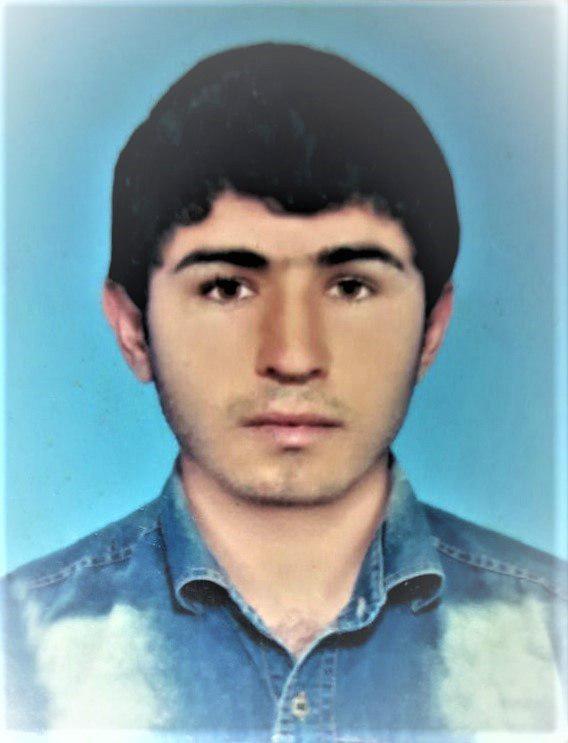

Saleh Shariati was sentenced to death solely on the basis of the sworn testimony of non-witnesses for an incident which took place when he was 16 years old. Based on reports received by Abdorrahman Boroumand Center (ABC) today, his family has been informed that the Supreme Court has confirmed his death sentence, raising concerns that he will be executed.

Fars Province Criminal Court One, Branch Three sentenced Saleh to death on the basis of qassameh in March 2016. Qassameh, a provision of Iranian law based in tribal pre-Islamic traditions which in the absence of sufficient evidence (clearly cited by the judge in Saleh’s case in his verdict) allows judges to sentence defendants on the basis of the sworn testimony of 50 of a plaintiff’s male relatives who need not have witnessed the crime in question.

When a young man fell down a well in Bushehr in 2012, Saleh happened to be standing near. Saleh was initially summoned as a witness to the death. 16 months later, for reasons unknown to his family, he was arrested as a murder suspect. The police held Saleh incommunicado and interrogated Saleh without the presence of an attorney and coerced him into confessing to murder. Authorities also transferred Saleh’s case from the location of the incident to the town where the plaintiff’s family resided, in violation of Iranian law. Saleh’s father reports that Saleh had lost weight and had marks of torture on his body when he first saw him after the arrest. Saleh claimed that his confession was coerced and by invoking qassameh, the court implicitly acknowledged that this confession was unreliable. Though no forensic or other evidence suggested the death had been an intentional homicide, the judge issued a death sentence for Saleh after hearing the oaths of 57 of the deceased boy’s male relatives.

The practice of qassameh by Iran’s judiciary has been harshly criticized by human rights observers, UN human rights experts, and the UN Secretary General. The Secretary General in his August 6, 2018 “Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Iran,” called explicitly for its abolition while citing Saleh’s case specifically.

Following the Supreme Court’s confirmation, only the granting of a retrial by the Supreme Court (a rare occurrence for such finally-confirmed cases) or pardon from the plaintiff’s family can prevent the implementation of Saleh’s death sentence.

If this sentence is not overturned, Saleh’s execution could be imminent. Iran’s judiciary has already put to death four juvenile offenders in 2018 (Abolfazl Chazani, Mahbubeh Mofidi, Ali Kazemi, and Amir Hossein Pourjafar) and 21 since the beginning of 2015 (including Alireza Tajiki, Bahram Ahmadi, and Arman Bahr Asemani). When questioned by members of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Iranian representatives had no convincing arguments to defend their continued policy of executing juvenile offenders:

WATCH: Iran & the CRC: Justifying the Unjustifiable

Abdorrahman Boroumand Center calls on Iranian judicial authorities to immediately void Saleh’s death sentence and grant a new legal investigation compliant with international human rights norms and Iran’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil Rights and Convention on the Rights of the Child. Iran’s parliament has ratified both agreements, which categorically prohibit the execution of minors.