“They bound your hands and feet. Then they hung you from a rod, like a piece of clothing, and kicked you in your stomach with their knees”

“They bound your hands and feet. Then they hung you from a rod, like a piece of clothing, and kicked you in your stomach with their knees”

Reyhaneh Jabbari, letter from Evin Prison (2014) Executed on October25, 2014

Today is the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture. June 26 marks the anniversaries of both the signing of the United Nations Charter in 1945 and the entry into force of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) in 1987. In 1998, the United Nations elected to mark this day to show solidarity with and commemorate victims of torture and to bring an end to this unspeakable crime.

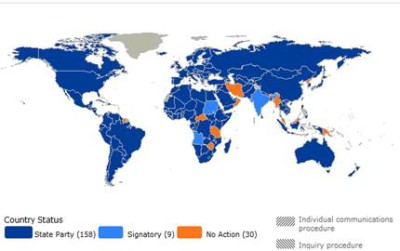

Status of Ratification of Convention Against Torture

-Source: http://indicators.ohchr.org/

The Convention Against Torture unequivocally bans all forms of torture under all circumstances including for reasons of national security and provides for remediation and redress for all victims of torture.[1] Iran is among the handful of countries in the world that are not state party to CAT. This is for good reason. The Islamic Republic flagrantly and routinely violates the treaty in its law, which prescribes corporal punishments such as flogging and amputation, and in practice.

ABF’s Omid Memorial records the cases of individuals killed by the Iranian state. While it does not systematically track cases of torture, many of the cases recorded in Omid contain instances of torture and ABF has collected and published the testimonies of scores of victims of torture at the hands of Iranian authorities. These cases illustrate how widespread and common the practice is.

Reyhaneh Jabbari Malayeri, for example, was arrested and eventually executed on October 25, 2014 on charges of murder, following a lengthy process rife with human rights and due process violations. In her seven years in prison, she was subjected to various kinds of psychological torture (humiliation, insults, obscene language, threats, her family members were arrested), as well as physical torture. She described her treatment in letters to her family:

"The chubby man pulled my head back, and the beardless man slapped my ears a few times: left, right, left, right. I experienced the first real thrashing of my life. ... I felt something in my back. I felt the swelling of my skin, and then ... rip.... my skin ruptured. I had a vision of my little sisters being made helpless like me. ... They bound your hands and feet. Then they hung you from a rod, like a piece of clothing, and kicked you in your stomach with their knees ...."

Ms. Malayeri’s experience is all too common. Iranian authorities frequently torture prisoners in detention, often with the purpose of extracting confessions. The Convention Against Torture not only bans torture in order to obtain confessions, but goes further in stating that any such confessions should not be admissible in court.[2]

Yet, Omid contains many cases in which torture was used to extract confessions.Bahram Ahmadi, was a Sunni activist who was arrested and charged with “waging war against God” at the age of 17. During his detention period, Mr. Ahmadi was frequently tortured. He told his cellmates that his interrogators used electric shocks, lashing, food deprivation, and threats against his family in order to get him to confess to having links to extremist groups whose goal was to overthrow the regime. At his trial, the confessions coerced during interrogations were used as evidence against him. In his will, recorded in prison, Ahmadi rejected all the charges against him as lies and insisted that his confession was only extracted through torture. Ahmadi was executed on December 27, 2012.

The fact that Mr. Ahmadi denied his confession had no bearing on the outcome of his case.

Indeed, Iranian courts have outright rejected defendants’ attempts to retract confessions made during torture. Hadi Rashei and Hashem Sha’baninejad, were arrested in 2011 in the wake of unrest in the Khuzestan province. Rashedi and Sha’baninejad were accused of involvement in a series of bombings that followed a police crackdown on citizens protesting the treatment of the Arab minority in Khuzestan. In custody, the two were subjected to various forms of torture, including flogging with cables, being hung from the ceiling, sleep deprivation, and mental and psychological pressure, as well as severe verbal abuse. To put an end to their torment, they confessed to the charges against them. However, when they came to trial they both retracted their confessions and expressly stated that those confessions had been dictated by security agents, that they were lies, and that they had been coerced into confessing under extreme mental and emotional duress and severe physical torture. Nevertheless, the Court convicted them and sentenced them to death. The Supreme Court upheld their conviction on appeal. A passage from the final decision issued by the Supreme Court reads:

“All of the defendants denied the charges against them at trial and declared their confessions before [the interrogators] to have been [obtained] as a result of torture as well as physical and psychological pressure. Further, they stated that their confessions before the investigating judge had been given under threats and through coercion by and in the presence of [law] enforcement agents. In spite of this assertion … the defendants and their counsel have not submitted any evidence to prove said claim … .”

More than just denying that torture has occurred within the Iranian judicial system, Iran has taken steps to assure that it continues. In 2002, the Council of Guardians vetoed a bill passed by the Parliament that aimed at limiting the widespread practice of torture and the use of forced confessions in criminal trials . The Council, a body of twelve senior clerics, judged that the bill would limit the authority of judges to adjudicate on the admissibility of confessions and therefore ruled that the bill was against the principles of Islam.

Indeed, torture is written into the Iranian legal system through the imposition of severe physical punishments such as flogging. At least 148 crimes are punishable by flogging. The laws related to flogging are broad and encompass a wide array of acts recognized as crimes. The criminal code recognizes corporal punishment (hadd and ta’zir) for offenses such as: consumption of alcohol, drug use and petty drug dealing, theft, adultery, "flouting" of public morals, illegitimate relationships, and mixing of the sexes in public. ABF maintains a database of cases of flogging and has records of more than 7,400 cases since 2000.

With the beginning of the fasting month of Ramadan in June, authorities, such as the Public Prosecutor in Kerman, are reminding Iranians that drinking, eating, or smoking in public will be punished with 74 lashes and up to two months in prison. Last year, the Prosecutor in Qazvin announced that 200 people had been flogged for eating during Ramadan.

Flogging is not the only brutal punishment inflicted by the Iranian state. Consider the case of Reza Safari. Safari was the victim of amputations twice, both for the crime of theft. In 1997, Safair had four fingers amputated from his right hand. In 2009, his left foot was amputated. In both cases, the amputations were performed with electric wire cutters without the use of local anesthesia or sterile equipment. Mr. Safari had not harmed anyone while steeling and the total value of what he had stolen in 20 instance of theft was a little more than $3,000. Unable to pay for what he stole, he was kept in jail years after finishing his 3-year sentence.

The Islamic Republic has long maintained that human rights are a Western construct, selectively applied to put international pressure on Iran and other countries that are out of favor with the community of Western nations. Iran has expressed reservations when signing international human rights instruments maintaining that when the tenets of those treaties run contrary to Islamic law, precedence will be given to Islamic law. However, Committee Against Torture[3] is explicit in rejecting any such claims of cultural relativism.[4]

The widespread and institutionalized practice of torture by the Islamic Republic of Iran is a clear violation of the spirit of international human rights law and the letter of the Convention Against Torture. On this day commemorating victims of torture, ABF unequivocally condemns the Islamic Republic’s violation of its citizens’ inalienable human rights and renews its call upon the Islamic Republic to immediately cease the practice of torture, to amend its legal code to formally outlaw the practice, to become a state party to the CAT, to take steps such as allowing defendants’ attorneys to be present during interrogation in order to ensure that this prohibition is enforced, and to put into place the means for past victims of torture to receive remedy and redress.

Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation

Washington DC

June 26, 2015

_______________________________________________________

[1] Article 1 - For the purposes of this Convention, the term "torture" means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

Article 2, which requires states to take the necessarylegislative, administrative, judicial or other measures to prevent acts of torture in any territory under its jurisdiction, recognizes no exceptional circumstances. States therefore, cannot invoke war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency to justify torture. The Committee against Torture “rejects any religious or traditional justification that would violate this absolute prohibition.”

[2] Article 15 - Each State Party shall ensure that any statement which is established to have been made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made.

[3] The Committee Against Torture (CAT) is the body of 10 independent experts that monitors implementation of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment by its State parties. The Committee also publishes its interpretation of the content of the provisions of the Convention, known as general comments on thematic issues.

[4] Article 2, paragraph 2, provides that the prohibition against torture is absolute and non-derogable. It emphasizes that no exceptional circumstances whatsoevermay be invoked by a State Party to justify acts of torture in any territory under its jurisdiction. The Convention identifies as among such circumstances a state of war or threat thereof, internal political instability or any other public emergency. This includes any threat of terrorist acts or violent crime as well as armed conflict, international or non-international. The Committee is deeply concerned at and rejects absolutely any efforts by States to justify torture and ill-treatment as a means to protect public safety or avert emergencies in these and all other situations. Similarly, it rejects any religious or traditional justification that would violate this absolute prohibition. The Committee considers that amnesties or other impediments which preclude or indicate unwillingness to provide prompt and fair prosecution and punishment of perpetrators of torture or ill-treatment violate the principle of non-derogability.