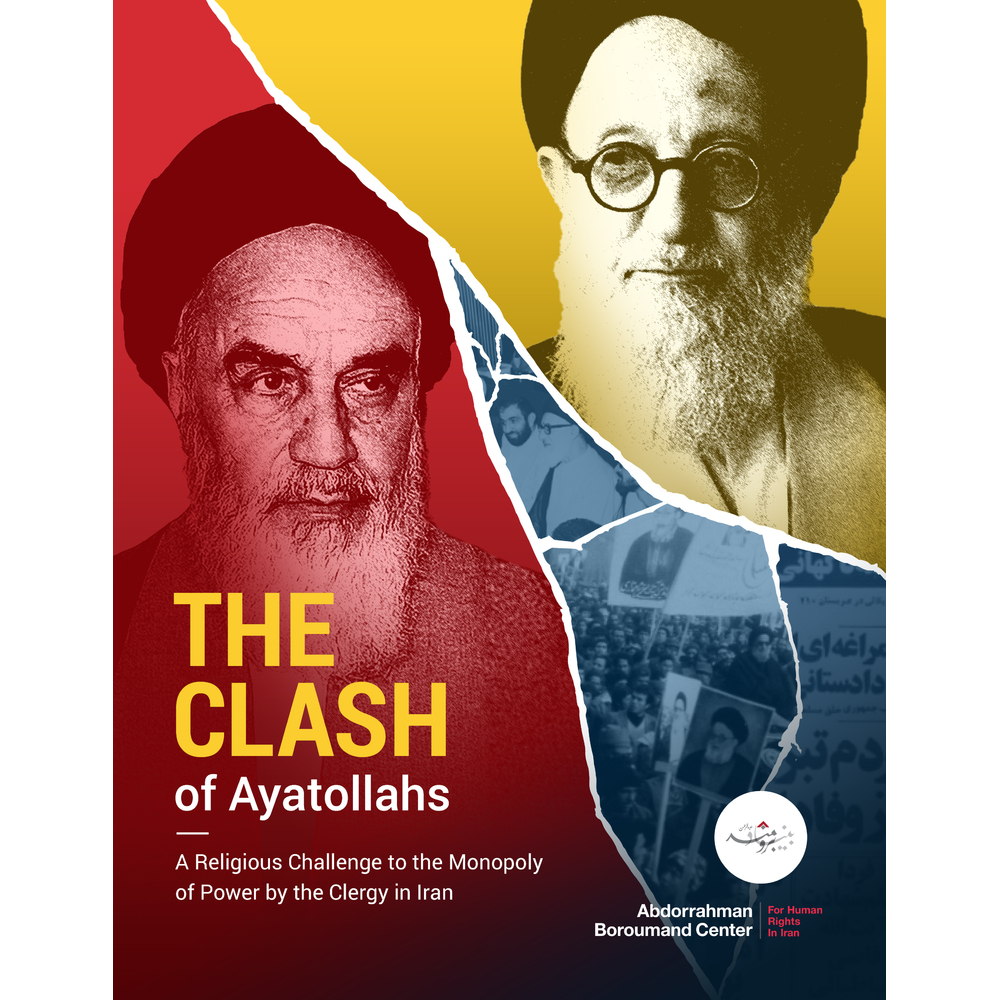

The Clash of the Ayatollahs: A Religious Challenge to the Monopoly of Power by the Clergy in Iran

Summary

Leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) dismiss critics of the country’s political system by claiming that the constitution, which grants ultimate and unchecked authority to an unelected religious leader, was born of democratic process. Their argument is enabled in part by the success of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his supporters in silencing their opponents and erasing a decisive moment from post-revolution history. Iranians of all walks of life and political stripes did in fact strongly oppose the revolutionary clerics' ambition to rule and Khomeini’s theoretical innovation of velayat-e faqih, or “guardianship of the jurist.” Khomeini’s most effective opponent, however, was Ayatollah Seyyed Kazem Shariatmadari, another influential cleric, who brought together a millions-strong opposition movement which rose in 1979 to prevent the establishment of the Islamic Republic as we now know it. When Shariatmadari and other opponents of clerical rule demanded the rule of law and popular sovereignty above all, Ayatollah Khomeini responded with electoral manipulation, censorship, threats, violence, and summary executions. At the end of a bloody six-week standoff between these two camps, the fate of Iranians was sealed in a theocracy, and the extensive public opposition to it was already being written out of history.

Iranians had indeed voted overwhelmingly in favor of an “Islamic Republic” - a form of government not yet defined - in the March 1979 referendum. In the months after, as forces loyal to Ayatollah Khomeini mobilized to ensure their vision of an unchallengeable religious rule, the initial revolutionary goodwill frayed, revealing fundamental differences in the aspirations of various religious and political actors, including Iran’s significant Sunni population. Helmed by the opaque Revolutionary Council which Ayatollah Khomeini had formed in exile, pro-Khomeini cadres worked to discredit, undermine, censor, co-opt, and intimidate their many challengers. The idea of a representative constituent assembly, expected by most, was dismissed in favor of a smaller, cleric-dominated Assembly of Constitutional Experts. Against a backdrop of machinations by the pro-Khomeini faction headed by the Islamic Republic Party (IRP) and massive boycotts from existing political groups, voter turnout in the August election of the Assembly dropped to less than half of the March referendum.

Assembly members, mostly loyal to the pro-Ayatollah Khomeini IRP, framed the new structure of power against a steady drumbeat of Ayatollah Khomeini’s invective against opponents of velayat, press closures, attacks on opposition meetings, and revolutionary trials and executions. As the outlines of the new constitution became clear, opposition mounted, including from the Muslim People’s Islamic Republic Party (MPIRP), formed with the blessing of Ayatollah Shariatmadari to fight the idea of a one-party political system. Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s support was formidable: between three and five million practicing Muslims, mostly of Azerbaijani descent, respected him as a source of emulation.

A hastily drafted constitution was hurriedly put to vote on December 2 and 3, 1979, amidst demands from across the political spectrum for time to debate and revise it, calls for boycott from most secular political parties, and serious tensions in provinces inhabited by minorities. Ayatollah Shariatmadari, who openly opposed the velayat-e faqih (enshrined in Article 110) and the fact that the constitution gave members of the Guardian Council the power to veto the parliament, also boycotted the referendum. Other Grand Ayatollahs, most of whom rejected the idea of clerical rule as dangerous to religion, did the same. By most accounts, the turnout was very low, despite official claims that 75% of eligible voters participated and voted massively in favor. The referendum neither eased the tension nor deterred opponents of the constitution from contesting it. Demanding an annulment of the vote and revision of the constitution, the MPIRP called a general strike for December 6 in Tabriz, capital of Azerbaijan, where pro-Shariatmadari protesters vastly outnumbered pro-Khomeini ones.

On December 5, pro-Khomeini elements in Qom attacked pro-Shariatmadari pamphleteers and Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s house, fatally shooting a volunteer standing guard on the roof. Anger mounted in already-tense Azerbaijan and among Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s followers in Qom and other cities. The unrest that ensued lasted more than five weeks. The protesters took over Tabriz, with the active and tacit support of most local revolutionary committees, armed forces, and the air force base, which prevented the central government from sending reinforcement to quash the unrest. Some leftist parties and groups stood behind Ayatollah Khomeini, prioritizing anti-imperialist struggle over the struggle for popular sovereignty and accusing the protest movement of harboring capitalists, elements of the former regime, and imperialist agents.

The unrest brought together villagers, laborers, merchants, truck drivers, students, clerics, and citizens of all walks of life, at times numbering more than a million at once, to Tabriz and Qom; their demonstrations there were met with assault and deadly fire. But Ayatollah Shariatmadari was no revolutionary and refused to escalate the confrontation. Fearing a civil war and bloodshed, he called his supporters to calm and withdrew his support from the protesters. By January 11, 1980, pro-Khomeini forces had crushed the movement in Tabriz and proceeded with a massive crackdown, beatings, imprisonments, property confiscations, executions, and assassinations. Ayatollah Shariatmadari himself was not spared: isolated, he was eventually put under house arrest and saw his religious establishment confiscated on trumped-up charges without trial. He was denied access to diagnosis and hospital treatment for what proved to be prostate cancer, which ended his life in 1986.

The Islamic Republic’s representatives and many observers valorize it as one of the few democratic orders of the Middle East, but the winter of 1979-1980 tells another story. Though not the final episode of Iranians contesting the terms of their constitution, it is unique in its scale and stakes, a suppressed and overlooked moment in Iran’s history that epitomizes and elucidates the most decisive tensions still playing out in Iran today. Four decades later, the clash of Ayatollahs Shariatmadari and Khomeini remains relevant as it sheds light on the nature of power in the Islamic Republic and questions the legitimacy of a constitution that blocks meaningful reform. Without changes to a constitution that essentially excludes them, Iranians seeking a more democratic polity will continue to grapple with intimidation, arbitrary arrests, and worse.

Background

Forty-two years ago in December of 1979, the newly formed Islamic Republic was institutionalized through a constitution that has irreversibly sealed the fate of the Iranian people in a theocracy. Through the concept of velayat-e faqih, or guardianship of the theologian, the constitution grants ultimate power to an unelected religious leader. Despite claims of wide popular support for the constitution from regime leadership figures including Ayatollah Khamenei, the current Spiritual leader of the Islamic Republic,[1] the constitution was widely contested. Many Iranians, civil society groups, political parties, and ethnic and religious minorities publicly took serious issue with each step of the flawed constitutional drafting process.[2] But the public and persistent oppositionof an Ayatollah, Sayyed Kazem Shariatmadari, Iran’s most influential source of emulation before the 1979 revolution, was the catalyst for a widespread movement against proposed constitutional articles that undermined national sovereignty. In galvanizing disparate forces, Ayatollah Shariatmadari and a several-million-strong opposition force became a formidable challenge to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his supporters’ attempts to monopolize power – a challenge that Iran’s new rulers could have overcome with either constitutional revision or violence. They chose the latter.

Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari was born to a religious family in Tabriz in 1906. He studied under reputable religious jurists in Tabriz and pursued his studies at the age of 19 in Qom Seminary, as Ayatollah Khomeini had done, and studied under Abdolkarim Haeri Yazdi, one of the founders of the Seminary. Following the death of Grand Ayatollah Borujerdi in 1961, Ayatollah Shariatmadari became one of the most followed Shi’a clerics in Iran, with very strong support in the bazaar as well as among landowners, villagers, the working class in Azerbaijan, and among Azerbaijanis living in other cities.[3] He also had followers in Pakistan, India, Lebanon, and some Gulf states. According to some estimates, Ayatollah Shariatmadari had close to 5 million followers, principally in Azerbaijan but also in Qom, Mashhad, and other cities where Azerbaijanis lived, affording him considerable influence and financial power in his religious activities.[4]

By the 1960s he had established in Qom the Dar-al-Tabliq, a religious institution that pursued apolitical missionary activities with modern communications means. His publication Maktab Eslam was the first official paper of the Qom Seminary. Ayatollah Shariatmadari was not a revolutionary, but he was a critic of the Shah and called for respect for the constitution. A long-standing tension divided Ayatollahs Khomeini and Ayatollah Shariatmadari: the latter held quietist beliefs[5] and, like most sources of emulation at the time, favored an advisory rather than executive role for clerics.[6]

The revolution did nothing to ease tension between the two clerics. When Ayatollah Khomeini put forward a referendum in March 1979 limiting voters to approving or rejecting the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Shariatmadari objected. Though he ended up participating in the referendum in support of the Islamic Republic, he disputed the referendum’s question, suggesting instead “Ask people what kind of a regime they want, and let the people respond.”[7] He also spoke out against the arbitrary behavior of the revolutionary committees (Komitehs), which were formed following the revolution to ensure security at the local level. Lacking a central authority and vested with extraordinary powers while the law enforcement forces were in post-revolutionary disarray, many Komiteh carried out arrests arbitrarily and were co-opted as instruments of terror by various political and religious actors.

Ayatollah Shariatmadari publicly criticized the secrecy, arbitrary rulings, and property confiscations of the revolutionary courts. He insisted that “defendants must be allowed a lawyer” and be tried by competent people.[8] The then Minister of Justice, Asadollah Mobasheri, also shared the Ayatollah’s concerns regarding the revolutionary courts from which judiciary judges were excluded. In a May 16 statement to a group of judges, he pointed out that since April 7, 1979, the judiciary’s judges had played no role in issuing judgments or reviewing cases.[9] The committees’ arbitrary arrests and the revolutionary court's summary executions were also reported by foreign observers.

Conducting months of field research into post-revolutionary arbitrary arrests, Amnesty International reported in 1980:

“It is clear that there was substantial doubt at this period whether persons in custody were those who, even under standards then applied, were guilty of offences. It is doubtful that Komiteh sources even knew who was in prison. It is certain that the Provisional Government remained in ignorance…There was no minimum protection against violation of the right to be free from arbitrary arrest…”.[10]

“Many Iranians,” reported a correspondent from The New York Times, “including some officials in the revolutionary Government, had expected that when the trials resumed, they would be public and would be used to demonstrate the evils of the Shah's regime. But the trials continue behind the closed steel doors of Qasr Prison. Often the only notice that someone is on trial is the announcement on the morning radio news that he has been executed. The front pages of the afternoon Persian‐language newspapers are filled with grisly pictures of the bodies.”[11]

After powerful clerics supporting Ayatollah Khomeini, such as Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti and Hojatoleslam Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, formed the Islamic Republic Party (IRP) on February 18, 1979, concerns about the likelihood of a totalitarian one-party political system grew stronger: IRP founders sought to sweep disparate forces into a single Islamic Party as the acting arm of the revolution. Concerned about the consolidation of a one-party political system based on an interpretation of Islam they did not share[12], a group of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters – political activists, influential bazaar merchants, and clerics – announced the formation of the Moslem People’s Islamic Republic Party (MPIRP), more commonly known as the Moslem People’s Party, in March. Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s son, Hassan, who on his father’s recommendation did not join the party, acted as a very influential advisor and intermediary between the party and Ayatollah Shariatmadari.[13]

The declared aim of the MPIRP was to rally “enlightened Muslim forces in the building of an ideal, progressive, and sovereign society, run by the people, guided by the principles of Islam, and adapted to the times.” The MPIRP declared that they would act and campaign to ensure that “the values and principles of Islam guide all aspects of life,” and that people’s fundamental rights would be respected. While Ayatollah Shariatmadari did not join or explicitly lead the party, he encouraged his followers to join,[14] and urged MPIRP founders to expand membership beyond his clerical and local following.

Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s support of the MPIRP provoked an immediate reaction from Ayatollah Khomeini’s supporters, in the form of an April 22, 1979, article published in Ettelaat daily by Sharia judge Sadeq Khalkhali – notorious for his aggressive capital prosecutions. Entitled “Excuses Should be Taken from the Hands of Traitors,” the article argued specifically that the existence of the MPIRP, and Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s support for it, indicated division among the religious leaders, which could be exploited by those opposed to the Islamic Republic. Offended, supporters of Ayatollah Shariatmadari, called upon by the MPIRP, responded two days later with their first real show of power in Azerbaijan and beyond, issuing statements, organizing mass street demonstrations, and closing down Tabriz.[15]

The growth potential of the MPIRP was facilitated by Grand Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s religious influence and prominence among Azerbaijanis across Iran. Over the years, thousands of fellow Azerbaijanis had studied under him in Qom’s seminary. Sustained by religious endowments to the Ayatollah, they returned to the mosques of their respective villages and cities in one of Iran’s most populous provinces and spread Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s religious teachings and political views. Heads of villages came in great numbers to the home of a member of the MPIRP leadership Council, according to his then 12-year-old daughter. “They stayed overnight and took stacks of membership forms to their villages and returned the forms filled and signed. We [the children] had the task of counting thousands of membership forms brought back.” Edalati, a high school literature teacher and a practicing Muslim, believed in the separation of religion and politics and thought, as many other practicing Muslims at the time, that the ruling clerics’ interpretation of Shari’a and the Qur’an was inaccurate.[16] Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s moderation, his opposition to arbitrary revolutionary justice and property confiscations, and calls for due process had also strengthened his influence among landowning, military, and Azerbaijani middle classes.

The MPIRP mustered a strong and diverse following among Azerbaijanis in cities such as Qom, Tehran, Ardebil, Hamedan, and Mashhad; it also drew members from the followers of Ayatollahs such as Qomi, Milani, Kho’i and Shirazi, some of whom declared openly their support for the new party.[17] The MPIRP called its members to vote yes in the Referendum on the Islamic Republic, taking issue with the constitution as the ruling clerics’ blueprint for the state became apparent.[18]

In the weeks following the February 1979 revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini and his supporters took further steps to consolidate their power. The secretive Revolutionary Council – whose members, predominantly clerics who still lead the country to this day, were handpicked by the Ayatollah in December 1978 – constantly undermined the provisional government with the blessing of the Ayatollah.[19] Revolutionary Council and IRP efforts to take control of the newly formed Sepah (Revolutionary Guards) were viewed with concern by many political and religious figures, including militant cleric and former Ayatollah Khomeini student Ayatollah Lahouti, who had been assigned the task of organizing the force. Lahouti resigned a few months later in November.[20] The development of public debate around the constitution shed light on irreconcilable differences in the interpretation of popular sovereignty, individual rights, and the role of Islamic jurists in government.[21] As the tensions mounted between the ruling clerics and more secular revolutionary groups critical of Ayatollah Khomeini’s attempts to monopolize power, the latter issued harsh warnings to any lawyer, writer, Western intellectual, or human rights activist thinking of opposing the clergy:

“That stratum which, because of its opposition to Islam, opposes us – they ought to be remedied with guidance, if it’s possible; if not, with the same fist with which you destroyed the [Pahlavi] regime, you shall destroy its affiliates… Sympathy does not mean you take up the pen to write something against Islam; that in the name of human rights or legal experts you go along with these people… Those who feel sympathy for the people in need, these human beings; these women on the outskirts of the city of Qom, the women of south Tehran… These are the people know human rights, and act [on it]… You should go along with these people… your pen, your actions, and your vote should agree with them; preserve Islam… do not oppose the clerics.”[22]

Constitutional Conflicts

By August of 1979, very few critics seemed to harbor any illusions about the political motives of the ruling clerics, and 20 political groups and ethnic and religious minority groups, along with Ayatollah Shariatmadari, opted to boycott the blatantly partisan elections for the Assembly of Constitutional Experts. The IRP, which benefited from wide access to national radio and television and means of propaganda according to an MPIRP leader, and whose followers disrupted the MPIRP gatherings in Tehran for example,[23] and the revolutionary guards exerted extensive control over the election process. They used a misleading format for electoral lists, for example, that confused voters about Ayatollah Khomeini’s support of their candidates[24] – and candidates complained about the undue interference of IRP representatives and violence at polling places.[25] The head of the Revolutionary Court in Tabriz acknowledged a few months later that some candidates had been subject to beatings in the August election.[26]

The MPIRP did not present an official list of candidates, prompting some of its founding members to resign. Other members meanwhile ran in the election as independents. The party held enough sway, as noted by Ayatollah Shariatmadari, to resist the impact of the resignations.[27]

On August 3rd and 4th, 1979, to draft a constitution for the newly established Islamic Republic, an Assembly of Constitutional Experts was elected in lieu of the larger and more representative constituent assembly that had been expected. In an interview in December 1979, Hojatoleslam Lahuti reported a 40% voter turnout, a sharp drop from the official statistics of 98% participation in the referendum of the previous March.[28]The low election participation rate reflected a sharp slip in citizen confidence in the political future being drawn by Ayatollah Khomeini and the militant clerics.[29]

Unsurprisingly, of the 72 members elected to the Assembly, 58 were clerics, most of whom, including the ten representatives from Tehran, were affiliated with the IRP. The Assembly’s Chair, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, and Vice Chair, Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti, were both staunch supporters of the velayat-e faqih concept.[30] Ayatollah Khomeini, who had called those who boycotted the elections “enemies of the revolution,”[31] paved the way for the establishment of a theocracy in his inaugural message to the Assembly’s members during their first session on August 18. He reminded them that they could not take into consideration any "proposals contrary to Islam,” as they would not be within the scope of their mandate. He further undermined the role of the few laypersons elected to the Assembly, limiting to leading Islamic jurists the privileges of both debate and decision on the compatibility of constitutional articles with Islamic criteria.[32]

Over the next three months, the Assembly of Experts debated on a constitution that would transform Iran into a repressive theocracy. Their talks took place against a backdrop of increasing censorship and restrictive press laws, sweeping closures of newspapers, rising execution rates, and attacks on opposition groups by pro-Khomeini militias. Ayatollah Khomeini maintained pressure on the Assembly of Experts and the public through his public statements and meetings. He regularly promoted the velayat-e faqih or the guardianship of the theologian principle (future Article 110 of the Islamic Republic constitution), which gave unchecked and ultimate power to him and his successors and attacked those opposed to it, including intellectuals and those who believed in the separation of religion and politics, accusing them of denying Islam and God.[33]

On August 7, the newspaper Ayandegan was closed down by the prosecutor general who announced that its editor would be prosecuted for “counter-revolutionary policies and acts.”[34] Known for its more impartial and thorough reporting, Ayandegan had been under attack for months by radical clerics and had seen several of its offices attacked by pro-Khomeini mobs.[35] On August 12, pro-Khomeini plainclothes militias, or hezbollahis, attacked a march mustered by nationalist and leftist groups who were protesting the closure of Ayandegan. Between 100 people, according to the Police Chief, and 270, according to the opposition groups, were wounded.[36] The militia also attacked a number of opposition groups’ headquarters.[37] The independent magazine, Peygham Emruz, was also closed, over accusations from the revolutionary prosecutor of publishing “seditious” news on the closure of Ayandegan.

The authorities did not spare foreign press either. A new press law was adopted to allow more control on the reporting of foreign correspondents, and the government ordered the New York Times correspondent in Tehran to leave the country.[38] On September 5, a reporter for the magazine Middle East was expelled, as was the correspondent of the Wall Street Journal on September 26.[39]

During the months of constitutional deliberations, the new revolutionary justice system was also stepping up executions. Steering the judiciary was close Ayatollah Khomeini ally Ayatollah Beheshti, who also happened to head the Revolutionary Council and serve as both the First Secretary of the Islamic Republic Party and the Vice Chair of the Assembly of Constitutional Experts. According to data recorded so far in Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights (ABC) memorial database, over the three-month period following August 2, 1979, execution numbers jumped 45% from 244 (May 3 - August 2) to 354 (August 2 - November 2).[40] Doubling down with the closure of 22 opposition-group publications by August 20, Ayatollah Khomeini’s supporters effectively stifled public debate on the constitution.[41]

The MPIRP, whose members in the Assembly of Experts were critical of the procedure and the draft constitution, addressed the “ruling group” in its weekly dated September 30, 1979, pointing out that a piece of paper carrying the “sacred name of ‘constitution’” does not have any value if it does not have the support of the people.[42] Concerns grew more acute when in mid-November, amid protests by a wide range of political actors, the Assembly of Experts concluded their hasty and closed deliberations over drastic revisions to the existing draft constitution. It was put to a popular referendum two weeks later.[43]

On November 25, in a statement published in Khalq Mosalman weekly,[44] the MPIRP announced that its participation in the upcoming referendum was contingent on the revision of the constitution:

“The Moslem People’s Party has stated that, in referencing the prepared text in the Assembly of Experts, it has noticed that there is no clarity to be seen in the matter of national sovereignty, and that this text, with its various problems, contradictions, and ambiguities, lacks the qualities necessary to be called a constitution. With the powers granted to the Supreme Leader, national sovereignty will be practically violated. How, therefore, can one vote in favor of a text whose articles violate one another? In this text, all powers are in the hands of one individual, who is not responsible to anyone, and responsibilities have been placed on people who lack the power necessary for and proportionate to them.”[45]

The MPIRP was not alone in calling for the draft constitution to be revised. Political groups across the political spectrum and Sunni minorities were either calling on Ayatollah Khomeini to delay the referendum on the same grounds or for a boycott of the referendum.[46] Ayatollah Khomeini rejected their demands on December 1, in “a message to the people of Kurdistan, Baluchestan and Turkmen Sahra.” The Ayatollah argued that the referendum could not be delayed, even for a few days, as “the great danger of unbelief was threatening the country and Islam.”[47]

Ayatollah Shariatmadari also joined the ranks of critics, pointing to shortcomings of the new draft and demanding revisions to the constitution’s more problematic articles. Of particular concern was article 110 – establishing the unelected Supreme Leader’s ultimate authority, either directly or indirectly, in all state affairs, including but not limited to policy delineation and implementation as well as the appointment, restriction, command, and dismissal of the President, Armed Forces, Guardian Council, head of the judiciary, and Islamic Republic Media bodies – which Ayatollah Shariatmadari believed contradicted articles 6 and 56, affirming the sovereignty of the people.[48] Without the latter, he insisted, Iran and Islam would be destroyed.[49] Only one newspaper, Ettelaat daily, published Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s statement. The Tabriz station of Iran’s Radio and Television network not only censored Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s communiqué, but proceeded to broadcast his picture over a statement from his brother Sadeq Shariatmadari encouraging people to vote. This subterfuge, which created confusion and led some of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters to participate in the subsequent constitutional referendum, further fueled tensions in the city.

Ignoring the persistent objections raised by numerous political and religious actors, a referendum was organized on December 2nd and 3rd of 1979.[50] Iranian officials claimed that 75% of eligible voters participated in the referendum. The real turnout, however, was low, including in Tehran: a correspondent from Le Monde reported empty streets in the capital and slim voting lines in two mosques he visited, which were located in poorer neighborhoods in the south of the city where voter turnout was expected to be high.[51]

Reports from Kurdistan indicate calls for revision and a near-total boycott of the referendum,[52] while in Azerbaijan – where the Governor claimed that 150,000 Tabriz residents had voted – unrest was reported for three days. In Baluchestan, where the governor declared that he considered his region’s 5% turnout “a success,” riots, armed clashes, and attacks on polling places were reported.[53]

Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a Revolutionary Council member and close ally of Ayatollah Khomeini, acknowledged in an interview with German TV that the referendum was boycotted by the leftist groups.[54] He failed to mention, however, critical details about the breadth and nature of the opposition, for example how groups such as the National Front and the Pan Iranist Party – questioning the legitimacy of the Assembly of Experts, the fairness of its proceedings, the authoritarian control of the Revolutionary Council (including over the Assembly’s election), and the ambiguity to the separation of powers and recognition of national sovereignty – had also called on Ayatollah Khomeini to suspend the referendum.[55] While conceding that there had been vo ter abstention among Sunnis and Turkish-language speaking Iranians who followed Ayatollah Shariatmadari, Rafsanjani omitted mention of the considerable opposition to the concept of velayat-e faqih among clerics, Ayatollahs, and grand Ayatollahs, including but not limited to Abolfazl Zanjani, Hasan Lahuti, Abdollah Shirazi, Mohammad Reza Golpayegani, Hasan Tabatabai Qommi, Morteza Haeri Yazdi, Abolqasem Khoei, and Ali Tehrani, some of whom had even refused to participate in the March 1979 referendum.[56]

Azerbaijan’s Anti-Constitution Uprising

The holding of the referendum did not deter Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s followers from insisting on the need to revise the problematic articles of the constitution. The MPIRP organized a general strike in Tabriz for December 6, where they would call for the annulment of the referendum and a revision of the constitution in support of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s views.[57] A French journalist stationed in Tabriz reported numerous groups and secular political parties supporting the action and preparing to convene at MPIRP headquarters the next day: the Social Democrat Iran Party, the Radical Party, the Fadayian Khalq (Marxist-Leninist), the Bazaar wholesalers, the civilian and military Personnel of Tabriz Air Force Base, and the teachers’ and students’ unions, among others. The pro-Soviet Tudeh Party and the Mojahedin Khalq (MEK) had sided with the Islamic Republic Party and Ayatollah Khomeini, prioritizing the anti-imperialist movement which they claimed rightist parties were trying to weaken.[58]

On December 5 in Qom, where Ayatollah Shariatmadari resided, counterprotesters – a group (Shahin) which, according to Hassan Shariatmadari,[59] was formed by Ayatollah Meshkini’s son and Ayatollah Khalkhali, with the blessing of Ayatollah Khomeini’s son, Ahmad – attacked the MPIRP protesters as they distributed leaflets. Tensions which began verbally near the shrine, where pro-Khomeini activists tore a leaflet, soon became physical and degenerated as the crowd moved towards Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s house. There, Ali Reza’i, a carpet maker and father of 3 young children who was among the guards volunteering to protect the house, was shot in the back as he stood guard on the roof. Reza’i died in the hospital. Several Ayatollah Shariatmadari followers were also hospitalized after being shot, stabbed, and beaten.[60]

Eyewitnesses and those injured reported being ambushed and assaulted after distributing their leaflets and noticing police and revolutionary guards among the crowd. Contrary to what the official media had reported, Ali Reza’i’s shooting was not accidental and did not come from the street. The mob, which hurled insults at Ayatollah Shariatmadari and chanted “the one who has not voted has lost the right to opine [on the constitution],” had tried to attack the house but were pushed back by guards. Some windows were broken. The weekly reporter for Khalq Mosalman, who visited the scene of the shooting, noted that the guards could not have been shot from the street. According to one of the employees of Ayatollah Shariatmadari, the shooter may have been on the roof of a neighboring house, where they found a ladder, a sort of barricade, and a hat.[61] According to Hassan Shariatmadari, an investigator on the case confirmed that police, after carefully modeling the bullet's trajectory [based on the victim's entry wound], determined it could not have been fired from the street.[62]

According to Le Monde’s reporter in Tabriz, the city was paralyzed on December 6 by a crowd of an estimated 100,000, including some military personnel, who took to the streets in support of Ayatollah Shariatmadari.[63] Violent clashes with the Revolutionary Guards were reported by the media. According to the daily newspaper Ettelaat, around 10:30 a.m. in front of Sardar Melli School, “20 to 30 people shot at some protesters passing through Shams Tabriz Avenue.”[64] The total number of casualties is unclear. A hospital reported that 2 people were killed and 6 wounded, but a representative for Ayatollah Shariatmadari said 4 people were killed and 30 wounded.[65]

Later, in Namaz Square, a gathering protested the attack against Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s house in Qom. Protesters called for the punishment of those responsible, the annulment of the referendum, and an end to censorship of radio and television. Some of the protesters walked to the Eastern Azerbaijan station of the National Broadcasting at around 2:00 p.m. and took it over. They interrupted the news program to announce the takeover of the station by supporters of Ayatollah Shariatmadari. Continuing their broadcast, they aired statements of support from other groups and the reiteration from Ayatollah Shariatmadari of the urgent need to revise the constitution.[66]

The station also aired an MPIRP statement demanding a say for Ayatollah Shariatmadari in the nomination of local officials. The statement demanded more rights for Azerbaijani peoples, and that they be granted the same rights as the people of Kurdistan. At the time, following a period of serious unrest the previous summer, the central government was in negotiations with Kurds regarding their demands for autonomy. The statement also called for the prosecution of the Qom attackers and the arrest of those responsible for the bloodshed earlier that day.[67]

On the evening of December 6, Tabriz seemed to be under the control of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters. The Governor, Prosecutor of Revolutionary Courts, and representative of Ayatollah Khomeini in Tabriz had disappeared from their offices, supplanted by pro-Shariatmadari committees. Additional government administrations had agreed to cooperate with the “new authority,” according to a reporter from Le Monde. The regular armed forces had retreated to their barracks while statements of support for Ayatollah Shariatmadari were reported from the Army personnel, Gendarmerie, Police, and Air Force in Tabriz.[68]

In Qom on December 6, while thousands of Ayatollah Shariatmadari supporters gathered outside his home,[69] Ayatollah Khomeini paid him a visit. He followed up later in the day with a public statement in which he condemned the attack, did not acknowledge the responsibility of his followers, and suggested that external forces were to blame – and to fear – for unrest and violence. He emphasized that people should be vigilant not to enable “foreign agents and the rotten roots of supporters of the former regime,” as “the dear country and the great Islam are facing the bloodsucking America.” Chalking up the attack on Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s house to the work of nondescript “plotters,'' he urged the public to “avoid divisive issues” and focus on the “great enemy.”[70]

December 6 also marked the date of an hours-long negotiation in Qom between Ayatollah Shariatmadari and a high-level governmental delegation including Mehdi Bazargan, Hojatoleslam Hashemi Rafsanjani, and Ayatollah Khomeini’s son, Ahmad. Prior to meeting the Tehran delegation, Ayatollah Shariatmadari called a press conference in which he expressed hope that condemnation of Ayatollah Khomeini would prevent the repetition of attacks. He reiterated his call for the revision of certain articles of the Constitution and his criticism of the articles that denied people power.

In response to journalists’ questions, Ayatollah Shariatmadari said that religious leaders must opine on the compatibility of laws with shari’a, but that it was unacceptable for laws to require the approval of the Constitutional Council[71] (or “Guardian Council” in Farsi) in order to be implemented.[72] He noted that the people who had taken over Tabriz’s broadcasting station and government offices had done so to demand power and more rights. Without using the word “autonomy,” he called for more provincial powers, which should be extended to the whole country.[73] On the whole, Ayatollah Shariatmadari seemed optimistic about reaching a resolution and asked that a delegation of the Revolutionary Council and his own representatives be sent to investigate the events of Tabriz and report back to him.[74]

As demonstrated by the messages of support he received following the December 5 attack on his home, Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s following was broad and diverse: telegrams came in from high-ranking clerics, such as Ayatollah Qomi and Ayatollah Khoi; Kurdish political and religious actors; various Tabriz revolutionary committees (Komitehs); residents of various Azerbaijan villages; workers, 2000 East Azerbaijan truck drivers, bus drivers, factory workers, guild members, and employees of various companies, including Azerbaijan Water and Electricity Company.[75]

Ayatollah Shariatmadari enjoyed the support of the majority of the region’s revolutionary committees (35 out of 43 committees in Eastern Azerbaijan, according to the head of the revolutionary tribunal of Tabriz at the time and 29 of the 36 committees of Tabriz)[76] as well as the military based in Azerbaijan, which appreciated Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s more reformist approach during the revolution.[77] All told, the national movement he embodied was estimated to be at least 3 million strong.[78]

The movement also had staunch secular opponents. The local branch of Fadayian Khalq, a Marxist-Leninist guerilla group with a strong base in Tabriz, had initially supported the movement, even though the influential representative of Ayatollah Shariatmadari in Tabriz, who had serious concerns about the growth of the communists in the city, had occasionally harassed them.[79] However, despite the fact that the group had boycotted the referendum on the constitution, its leadership decided to withdraw support from the MPIRP, describing it as “reactionary and an agent of imperialism.” Two other major groups also condemned the unrest as an imperialist plot to weaken the anti-imperialist movement in favor of US interests: the pro-Soviet Tudeh Party, which had supported the Assembly of Experts of the Constitution candidacy of the first Shari’a judge, Sadeq Khalkhali, whom they praised for his “unparalleled courage” in “sending to the gallows several hundred of the most important imperialist pawns”[80] and had called for a yes vote to the constitution, and the Mojahedin Khalq Organization, who had boycotted the constitutional referendum but did according to some activists, join the pro-Khomeini forces in the attacks against the pro-Shariatmadari forces.[81]

During the unrest, Nureddin Kianuri, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Tudeh Party of Iran provided the members the party’s rationale for opposing the anti-constitution protest in Tabriz:

“In our view, the Khalq Mosalman Republic Party, which is run by big capitalists and hooligans related to the despised regime of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, have misled some people using deceiving slogans, people’s religious beliefs, and a series of populist actions and protests, and they have managed to stir up unrest…. [Knife-and-stick-wielding street thugs of the former regime] are using the religious influence of Ayatollah Shariatmadari to direct the popular movement on a reactionary and deviationist path that is harmful to Iran’s revolution.”[82]

Ayatollah Shariatmadari and the MPIRP were nonetheless effective in galvanizing forces across the political spectrum, including among the local sympathizers of the Fadayian Khalq and the Ashraf Deghan’s splinter group. The MPIRP rejected the communist groups’ accusations and reiterated the Party’s anti-imperialist convictions while emphasizing that it would “not allow Khomeini to establish a dictatorship under the cover of his anti-imperialist struggle.”[83]

On the evening of December 6, political groups continued to struggle for control of the national broadcasting station in Tabriz, which aired statements by Revolutionary Council Member and Head of provisional government Mehdi Bazargan, who accused Tabriz protesters of being “leftists” and “anti-revolutionaries.” The broadcast prompted pro-Shariatmadari protesters to occupy the station again, without clashes, according to The New York Times. They responded to Bazargan on the radio and television, refuting his accusations and reminding him of the specific events that had triggered the protest.[84]

Other clerics backing the MPIRP spoke publicly on behalf of the party’s objectives. One cleric outside the station lectured to a gathering of thousands about the “dictatorial character” of the new constitution, while another cleric inside the station offered the press his own response to Bazargan’s accusations, stating that he recognized Ayatollah Khomeini not as the sole leader of the revolution, but as one among many. He called for more widespread respect of the views of Ayatollah Shariatmadari and insisted that the opposition movement aimed at “strengthening the foundations of the Islamic Republic by eliminating deviations.”[85]

That same evening, the station, still under MPIRP control, broadcast statements from both Ayatollah Shariatmadari and the MPIRP deploring the attack on Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s house. The broadcast urged followers to remain calm, avoid situations that might provoke clashes, and be patient for “the sake of Islam and to protect the Islamic country.” The next day of December 7 in Tabriz passed in relative calm. Shops were open, and the local broadcasting station read statements of the MPIRP among others in between Quranic verses. In Rah Ahan Square,supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini gathered for the Friday sermon and chanted pro-Khomeini slogans.[86]

However, the crisis between the opposing Ayatollah’s cohorts resumed the next day and continued to escalate through the second week of December. Tensions were left to simmer further as various government representatives, including Ayatollah Khomeini himself, made visits to the city and proffered expressions of solidarity but failed to follow up with concrete concessions or compromises. A group of four to five hundred people marched from Tabriz University towards Imam Khomeini Avenue on the morning of December 8, holding photos of Ayatollah Khomeini and alternating between pro-Khomeini slogans and slogans condemning “hypocrites serving America.”[87]Meanwhile, supporters of Ayatollah Shariatmadari, which also included a majority of the military personnel in Azerbaijan,[88] prevented the provincial governor from regaining control of the statehouse. The air force base in Tabriz and Orumieh, where pilots had already disobeyed orders from the central government to help quash the unrest in Kurdistan, refused landing to an airplane that was believed to carry government troops.[89]

On December 8, Ayatollah Shariatmadari reminded Mehdi Bazargan via telegram that he had succeeded in mitigating public tension in Azerbaijan, but that the government had failed to follow through on its promises and that government representatives continued to make inflammatory statements. He stressed that if the situation continued, he “would not be responsible” for what happened in Azerbaijan.[90]He then dispatched a delegation to Tabriz to investigate the situation, including at the radio and television station. That evening, he had a 30-minute private meeting with Ayatollah Khomeini at the latter’s residence, which he described as “good and effective.”[91]

One of the inflammatory statements Ayatollah Shariatmadari may have been referring to was that of Interior Minister Hashemi Rafsanjani, in an interview he gave on the evening of December 6: in the daily newspaper Ettelaat, the latter minimized the grievances of Ayatollah Shariatmadari as resentment over “not being consulted” in decision-makings about Azerbaijan and warned Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters to vacate the radio and television station. [92]

The two cohorts continued to contend for control of the National Broadcasting station in Tabriz on December 9. In the morning of that day, Radio Tabriz programs were interrupted when one of the transmitters, deliberately damaged by station personnel in the early hours of the morning, caused the station to go silent. That afternoon, students and militiamen loyal to Ayatollah Khomeini drove Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters out of the station. Hassan Shariatmadari and activists present in Tabriz at the time point out that access to the station played a crucial role in the struggle. A number of times that Tabriz protesters or MPIRP members found themselves under siege, people responded to their calls for support over the radio by showing up in significant numbers and causing their attackers to retreat.[93]

Later that evening, after the transmitter damage was repaired, a statement by Ayatollah Shariatmadari was aired. The statement announced continued negotiations between himself and representatives from the Revolutionary Council and asked his supporters to remain calm and not participate in demonstrations while a mutual resolution was sought.[94]

Late on December 9, the station was reclaimed by Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters, according to the media, though the reclamation had come at great cost:

“Today's clashes” reported The New York Times, “began with a rush on the radio and television station by followers of Khomeini, who routed armed supporters of Shariatmadari, who in turn fled without firing when a large crowd broke down the fences surrounding the transmitters and fired into the air. Later in the afternoon, Shariatmadari's loyalists regrouped and mounted a fresh attack on the station but were met by heavy firing from Khomeini's forces. Eyewitnesses near the station said they saw ambulances racing between the scene of the fighting and hospitals in the city of 500,000.”[95] According to the Associated Press reporter, pro-government militiamen opened fire into an unarmed crowd killing three young men and wounding 60, 23 of them critically.[96] Statements from local government officials regarding casualties from the clash “on both sides” were vague and minimized the number of people injured.[97]

In a statement on December 8, the head of the Gendarmerie had declared support for Ayatollah Shariatmadari and announced that it would ensure protection of the broadcasting station, which was “public property.”[98] Late in the evening of December 9, it appeared that the Gendarmerie had taken peaceable control of the station:

“ … The Government’s radio and television station was being guarded by local units of the Iranian Army, but both supporters of the Turkic faction led by Ayatollah Kazem Shariat-Madari and students and militiamen professing loyalty to the Government under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini appeared to be moving freely in and out of the hilltop facility.” [99]

In the midst of the confusion, continued negotiations between the two Ayatollah’s camps did not unfold as planned. Rather than the agreed-upon joint investigation led by Premier Bazargan, a three-man delegation, composed of Minister of Economic Affairs Abolhassan Banisadr, Ayatollah Mahdavi Kani, Chief of the Central Provisional Committee, and Ezatollah Sahabi, a member of the Revolution Council, arrived in Tabriz. Banisadr stated that the delegation would not negotiate with the MPIRP, adamant that it intended instead to “talk to all Azerbaijanis and not to any one specific group.”[100]The delegation was not interested in hearing about the problems in Tabriz, according to an MPIRP leader in Tabriz. “Banisadr angered people with his speech and Mahdavi Kani kept saying ‘make peace.’”[101]

Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters maintained their strongholds in Tabriz on December 9. The state house was still occupied by the MPIRP, which claimed to be in charge in Tabriz and vacated the building that evening voluntarily. Declaring a three-day mourning period for the shooting victims, the MPIRP called on shops to keep closed. The directive was followed by many shops and “virtually all schools,” according to the AP reporting from Tabriz, suggesting a restored calm.[102]

In Orumieh, however, pro-government forces took over the MPIRP headquarters and took several party members hostage, triggering a new pro-Shariatmadari protest. Protesters were shot later that evening when they gathered in front of the Party’s headquarters calling for the release of the hostages. According to the daily newspaper Ettelaat, which would later report the release of the hostages, two protesters were wounded in the gunfire.[103]

On December 10, Ayatollah Shariatmadari – in face of pressure from Ayatollah Khomeini, who claimed that the MPIRP was a foreign invention,[104] and from scholars of the Qom Seminary who in a letter (published before being received by Ayatollah Shariatmadari) were urging him to dissolve and deny association with the “anti-Islamic” Muslim People’s Party – wrote an emphatic open letter to Ayatollah Khomeini denouncing the bad faith of the government: “Today it is the turn of the Moslem People's Party, tomorrow it is the turn of other parties. They want to make all these parties step aside to have one single party and we will not accept it.” He noted that the government had broken their agreement to a joint investigation into the events of Tabriz.

While Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s letter, which was prevented from being broadcast or printed, was distributed as leaflets by his followers,[105] Ayatollah Khomeini’s statements decrying the Tabriz protest as a “rebellion against the rule of Islam” received wide national coverage.[106] He addressed those he accused of summoning villagers to a “holy war:” “You wage a holy war so that Carter can be successful and take your country over? Those who come and say so are lackeys of the embassy and its affiliates.” He added that the “corrupt” people backing the Tabriz uprising “were opposed to Islam from the very first day.”[107]The New York Times reported that marches in support of Ayatollah Shariatmadari and in protest of the new constitution continued in Tabriz on December 13. Protesters also expressed outrage at national broadcasting for airing false information, including accusations of imperialism and Zionism against the people of Azerbaijan, and chanted slogans criticizing the constitution as “inhuman,” or stating “The world should know, Khomeini is our leader, but Shariatmadari is our source of emulation”[108] Demonstrators numbered in the thousands, according to The New York Times; the daily newspaper Keyhan reported one and a half million. After the march, protesters gathered in a Tabriz square and read a ten-point statement, which included:

- approval of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s latest responses to clerics’ open letter,

- a statement of support for the MPIRP

- the demand for revision of Article 110, “as requested by Ayatollah Shariatmadari”

- release of all political prisoners, including those arrested in Azerbaijan or elsewhere in relation to the events of Azerbaijan

- recall of revolutionary guards who had been sent to Tabriz to intervene in the affairs of Azerbaijan.

Protesters also demanded that Ayatollah Shariatmadari be given a say in the nomination of political and religious leaders, that the revolutionary guards who had shot protesters dead be prosecuted, and that the judiciary and revolutionary courts adapt to both progressive standards and the shari’a.

One cleric, among others present in the protest, insisted that they were not counterrevolutionaries or secessionists, and that there were no foreigners among them, stating “We are Muslim and revolutionary.” The cleric also pointed out that the national radio television had given ample airtime to clerics' criticisms of protesters without ever broadcasting the statements of Ayatollah Shariatmadari.[109]

On December 15, the Public Relations Office of the Revolutionary Guards of Qom released a statement announcing the arrest of one of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s guards for the December 5 murder of the guard on the latter’s roof. [110] The arrested guard was tried two months later. According to the revolutionary court of Qom, he was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to pay blood money based on “evidence and testimony.” Details on the nature and extent of evidence against him were left unexplained, leaving serious doubts regarding the guilt of the accused.[111]

On December 16, the newspaper Enqelab Eslami reported that two members of the provisional government, Bani Sadr and Sanjabi, were back from a five-day trip to Tabriz where they were to hear the grievances of a diverse groups of residents and report them back to the Revolutionary Council and Ayatollah Khomeini. According to Banisadr, most residents complained about the policies of the radio and television, which did not broadcast the truth about events in Tabriz.[112]

Though detailed reports on what happened in the last two weeks of December and early January are scarce, it is clear that clashes continued between the revolutionary guards and other anti-Shariatmadari forces and pro-Shariatmadari protesters. While the clampdown on independent news sources continued with the expulsion from Tehran of a reporter from the Associated Press[113] and two correspondents of Time magazine,[114]pro-government revolutionary guards attempted to take over the MPIRP headquarters in Tabriz.

Once on December 17,and once again on the night of December 27, revolutionary guards attempted to take over the MPIRP headquarters in Tabriz without success. “The scuffle” wrote the Associated Press (AP) reporter from Tabriz, “grew into a nightlong gunfight that wounded at least five persons and left the three‐story building pocked with bullet holes.” Party supporters and militias loyal to Ayatollah Shariatmadari pushed back the attackers and took 9 revolutionary guards hostage. In return for releasing the hostages, the MPIRP demanded the release of some 200 local people arrested two weeks before. A militiaman who did not want to be identified for fear of government reprisal told the AP reporter: “We don’t want brothers to kill each other, but we want those people that were arrested to be released, and then we will release these nine.” [115]

With Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s intervention, the MPIRP agreed on principle to release the hostages under certain conditions, such as the replacement of local officials with those approved by Ayatollah Shariatmadari, the elimination of Article 110 of the constitution, and a greater role for the MPIRP in government.The incident prompted the East Azerbaijan Governor to visit Ayatollah Shariatmadari in Qom to negotiate release of the hostages.[116]

On January 4, 1980, unrest in Qom by Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters – who had arrived in 40 or 50 buses from Esfahan, Qazvin, Shahrrey, Tehran, and Karaj to visit Ayatollah Shariatmadari – radicalized the confrontation. A group of visitors who had gathered around Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s house in Qom was attacked by a group of people armed with knives and other deadly cold weapons who were attempting to surround the residence.[117] Supporters of Ayatollah Shariatmadari defended themselves and beat the attackers into retreat, according to Hassan Shariatmadari, before marching towards Ayatollah Khomeini’s house. Concerned about bloodshed, Ayatollah Shariatmadari calmed his supporters and prevented them from attacking Ayatollah Khomeini’s house by recording a message on cassette that was played over a squad car loudspeaker.[118]

On January 8, a joint communiqué of the Police, Gendarmerie, and Revolutionary Guards announced the placement under strict control of all the entrances to Qom, warning citizens against suspicious behavior or carrying any arm, and advising them that any attempts to cause unrest would be punished. Prosecutor General Qodusi also published a statement announcing the creation of a special prosecution group with the aim of avoiding repetition of the January 4 incidents by anti-revolutionaries. The New York Times reported that the residence of Ayatollah Shariatmadari was also surrounded.[119]

According to Hassan Shariatmadari, in a meeting between Ayatollah Shariatmadari and Ayatollah Khomeini, the latter threatened to bombard Tabriz,[120] as he had done to quash unrest in Kurdistan a few weeks earlier. His son, Ahmad Khomeini, conveyed a similar message to Hassan Shariatmadari at around the same time.[121] Ayatollah Shariatmadari, who, according to people close to him, did not approve of violence and was intent on avoiding bloodshed, decided to yield to the mounting pressures in hopes of defusing the crisis. In a statement reported on January 6, Ayatollah Shariatmandari said that if the Muslim People’s Party continued to operate it would “not be approved by me at all.”[122]The statement did nothing to appease protesters in Tabriz, where the government had done nothing to de-escalate the tension.

On January 6, after a 24-hour calm, demonstrators again marched in Tabriz before gathering in front of MPIRP headquarters and declaring their support to the party and to Ayatollah Shariatmadari. On the 6th and 7th, most shops and businesses – some encouraged, according to the daily newspaper Kayhan, by stick-and-stone yielding youth – and most schools were closed.[123] On the 7th, pro-Shariatmadari protesters attacked and set fire to the office of one of the pro-Khomeini committees, komiteyeh Bazresi, which according to a political activist had been one of the most aggressive and had arrested some of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters.[124] No casualties were reported; a member of the Bazresi committee reported that the offices had been vacated.[125] The New York Times reported that street fighting between supporters of the two Ayatollahs in Tabriz had left one person dead and hundreds injured.[126] On January 9, 1980, continuing unrest, which shook Tabriz for several hours, resulted in heavy casualties. Media reports indicate 10 people died and a hundred more were injured after revolutionary guards fired on supporters of Ayatollah Shariatmadari during a demonstration[127]. According to a Kayhan reporter stationed in Tabriz, the supporters of both Ayatollahs marched and gathered in the city.

On the next morning of January 10, two separate protests formed in support of Ayatollah Khomeini and Ayatollah Shariatmadari, with the latter ending in tragedy. To a crowd of Ayatollah Khomeini supporters in front of Tabriz University, Head of Tabriz Islamic Revolutionary Court Hojatoleslam Seyyed Hosein Musavi referred to pro-Shariatmadari protesters as “leftovers of the dirty Pahlavi Regime,” warning that insults to the Leader or sanctities would no longer be tolerated: “Anyone causing disturbances in the city will be arrested and sentenced to death.”[128]

Pro-Shariatmadari protesters gathered in front of MPIRP headquarters eventually split into two separate groups, one marching toward the Bazaar and the other headed to Tabriz University around 11:30 a.m. There, pro-government forces, including the revolutionary guards, used tear gas and opened fire. The daily Kayhan reported that the shooting lasted for an hour, killing a number of protesters and injuring many more. The fleeing protesters burned several banks, cars and phone booths; meanwhile, pro-government revolutionary guards attacked a pro-Shariatmadari committee office, opening fire on it for 3 hours before taking it over at 8:00 p.m. Keyhan and other sources reported deaths and injuries incurred by this second round of shooting, though the exact number of casualties is unclear.[129]

According to an eye witness, the shooting between pro-Khomeini revolutionary guards partially surrounding the building that housed the MPIRP headquarters on the one hand, and a pro-Shariatmadari committee defending the building on the other, was so intense that he and a friend had to take cover in a dry river bed nearby, where they saw two protesters in their twenties, "one shot dead and one injured. From their clothes, they were ordinary people. The intensity of the shooting was such that we had to flee. I don't know if anyone was able to move the injured protester." The next day, the day they took over the MPIRP headquarters, "we didn't dare go there. My father said don't go out of the house.” Armed pro-Khomeini forces had filled the area.[130] According to available information, violent clashes had in fact continued into the next day of January 11, and the takeover of the MPIRP headquarters by pro-government revolutionary guards, who used RPG7s. At least four people died, according to the New York Times.[131]

On January 12, the revolutionary guards released a statement to the media announcing the takeover of “the last bastion” of the MPIRP during the night, and the arrest of people who “had past records of various crimes, were mercenaries of foreigners, and carried out anti-revolutionary activities there on the order of traitors to the religion.”[132] The communiqué did not announce the number of MPIRP casualties, but noted the “martyrdom of one Revolutionary guard.” At the same time, the Revolutionary Court of Tabriz announced the names of 11 people who had been executed at 8 a.m. for “causing fear and disruption among people, arson and stick-wielding, armed uprising against the Islamic and Quranic Regime, murder and torture of Tabriz Muslim people, waging war against god and god’s prophet, and murder of God’s people.”[133] No other details were provided in the statement. In its reporting of the incident, The New York Times noted that the eleven men were captured, tried, and executed the same day.[134]

Authorities then moved aggressively to exert control over subsequent press coverage of events in the country. Tabriz authorities banned all foreign journalists from the city on January 11,[135] while East Azerbaijan Governor Nureddin Gharavi, citing foreign correspondents’ reporting of casualties and their “shameless analysis,” announced that he had ordered all foreign correspondents landing in Tabriz to be sent back to Tehran immediately.[136] The Revolutionary Council followed up with an order for all journalists working for US news organizations to leave Iran by January 18.[137]

In the weeks following the quashing of the unrest, the judiciary set out to punish protesters with severity. Head of Tabriz Revolutionary Court Hojatoleslam Musavi stated that 150 people had been arrested in the unrest, which he attributed to the acts of “hooligans acting under the guise of religion” and “individuals affiliated with the Pahlavi Regime and the SAVAK, fugitives, capitalists, and leftist agents.”[138]A few days later, Musavi accused 50 officers and commanders of Tabriz Air Force base, 30 of whom had already been arrested, of “plotting.”[139] He also accused the freemasons of being behind the unrest.[140]

The trial of three of the 22 military personnel arrestees, which began on January 20, 1980, in the Great Mosque of Tabriz Police Force Prison, was a blatant violation of due process of law. As reported by the media, the three court sessions that took place were presided by Shari’a Judge Hojatoleslam Mohammadi, dispatched from Qom, an unnamed colonel, and a major. The prosecutor demanded the court convict the defendants as “corruptors on earth,” a charge which carried the death sentence. The three air force officers – First Sergeant Siruz Pazireh, First Sergeant Akbar Abdollahi, and Major Mirheydar Mokhber – were accused of insulting their “superior and participation in the detention of the Commander, conspiracy against the Islamic Republic of Iran, detaining the Base Commander, disobeying orders, uprising against the Army of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s command, and creating chaos and disorder in the Base.”[141]

All three men, denied the right to a lawyer, rejected the veracity of the charges against them and presented their own defense. The media reported that the prosecutor mentioned “evidence” and “testimonies of witnesses” to substantiate the charges, but no information is available on the nature of the alleged evidence or witness testimony. Based on the testimony of one eyewitness, the crime of the defendants amounted to detaining the base Commander for two hours – during which he was not harmed – in protest of the latter's request to arbitrarily detain a soldier at the police station. “Does this deserve a death sentence?” the eyewitness noted. “No. They were [punished] because they were supporters of Shariatmadari.”[142]

Close to six weeks after it had begun, the most formidable challenge to the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic’s constitution by the country’s Shi’a clerical establishment – led by Ayatollah Shariatmadari against a backdrop of unrest among Iranian Kurds, Baluchs, Turkmens, and Arabs concerned about their place in the laws of the newly founded Islamic Republic – had been violently crushed. The crackdown resulted in at least 17 executions, including merchants and air force officers, the imprisonment of scores of activists, merchants, and villagers, and the imprisonment and defrocking of several clerics accused of “incitement against the revolution and active participation in anti-revolutionary activities of the Khalq Mosalman Party [MPIRP], slander, moral corruption, and attack of the radio and television.”[143]

According to available information, at least 41 people were killed during the Tabriz unrest and hundreds were injured. Close associates of Ayatollah Shariatmadari received death threats, were coerced into cooperation, and worse. On January 10, 1980, Doctor Mohammad Baqer Sadaqiani, an influential follower of the Ayatollah and a very wealthy and popular doctor in Tabriz who treated the poor free of charge, was kidnapped and shot multiple times before being abandoned on a road 32 km away from Tabriz. The group claiming responsibility for putting him on trial and executing him, “The Guerilla Organization Fajr Mostaz’afin,” alleged they did so because of his involvement in the events of Tabriz and Qom. The same accusation had been made by the head of the Revolutionary Court of Azerbaijan, Seyyed Hossein Musavi Tabrizi, and published two days prior in the Islamic Republic daily, the organ of the IRP.[144] Hojatoleslam Sheikh Morteza Mahmudi, a 45-year-old member of Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s staff in Qom who wrote all of his communications, was also shot dead near his home on May 4, 1980. Available information suggests that in the case of Mahmudi, three people, Ali Sadeqi, Sa’id Feqh Meshkini, and Mohammad Mehdi Janati, were arrested. But there is no indication that prosecution took place in either of these cases.[145]

At least one of the MPIRP leaders who managed to flee the country, Edalati, was tried in absentia and sentenced to death and property confiscation by Musavi Tabrizi. His family members were also punished. His wife, who was also a teacher, was fired from her job and his daughter was not allowed access to university, despite her good performance in the university entrance examination.[146] Another member of the MPIRP leadership, Ali Asghar Khosravi, reports having escaped a kidnapping and possibly an assassination attempt.[147]

Ayatollah Shariatmadari’s supporters in Azerbaijan were pressured to repent. "The city had become a security zone. For 10 years, no one dared to speak. They opened criminal cases for many people; if they recognized anyone on the street, they would beat them badly; they brought pro-Shariatmadari clerics to mosques to repent and say that, for example, 'We didn't know that Shariatmadari was an agent of imperialism,'” a witness told ABC.[148] One influential Ardebil cleric, Ayatollah Sheikh Ahmad Payani, was detained for three days and received death threats to declare support for Ayatollah Khomeini. Even in more remote villages, Ayatollah Shariatmadari supporters were under great pressure. A supporter who resided in a village outside of Ardebil told ABC that pro-government clerics and guards harassed villagers, demanding they acknowledge Ayatollah Khomeini’s authority and insult Shariatmadari, and beat and threatened those who refused. To one village elder, who refused to insult Ayatollah Shariatmadari, they said they would take him away in the trunk of the revolutionary guards' car. In some instances, they degradingly colored the beards of village elders who refused in red.[149]

Ayatollah Shariatmadari himself was silenced and his teaching activities restricted. In a move described as unprecedented in Shi’a religious jurisprudence, clerics of the Qom Seminary Scholars Community, who were mostly Ayatollah Khomeini’s students, eventually defrocked him in the spring of 1981, through an unsigned statement dated April 20, 1981. He was accused of complicity in a plot to assassinate Ayatollah Khomeini – an allegation based on sketchy evidence that was never presented in a proper judicial proceeding – and placed under house arrest. The closest process he had to a legal trial was a televised interrogation in his home, aired on national television, of which he later said his responses were censored. Darol Tabligh, the wealthy institution he founded to carry out his religious activities and publications, was taken over by supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini without apparent legal basis.[150]

The dissident Ayatollah died of cancer in April 1986 after being denied adequate medical care for years. Symptoms of cancer had been detected by doctors a few months into the house arrest, but repeated pleas to allow hospitalization and a biopsy for proper diagnosis, staging, and treatment were ignored. According to Hassan Shariatmadari, a transfer to Qom’s Nekui Hospital, ordered by the Ayatollah’s doctor, was cancelled on the order of Ahmad Khomeini. Only three years later, after the untreated prostate cancer had spread and seemed terminal, was Ayatollah Shariatmadari hospitalized.[151]

Conclusion: A Fight that Never Ended

In the year after the revolution, secular and religious Iranians challenged the revolutionary rulers' conception of the state and the constitution. Their efforts were ignored, dismissed, censored, and silenced through threats, censorship, and physical violence. The uprising brought about by Ayatollah Shariatmadari was a prodigious challenge to a constitution denying citizens the right to bring about meaningful changes in their country’s laws and governing system. This challenge was not overcome democratically, but through electoral fraud, intimidation, and violence, all of which continued to silence critics during the first decade of the revolution.

Nevertheless, in the proceeding years, when the country’s political space showed some opening, secular and religious Iranians have challenged, often at great personal cost, the constitution. They decry the political impasse constructed by a constitution where the will of the people is subordinate to the will of unelected leaders who claim to derive their legitimacy from God. They have demanded the revision of the constitution, or a new constitution altogether.

Lawyers have pointed out the legal obstacles to reform and the ambiguity of “Islamic principles, which provided a fertile ground for authorities’ arbitrary interpretation of laws,[152]” but they have not been alone in their criticisms. Students have criticized the absolutist power of unelected leaders;[153] activists have demanded a new constitution based on the UN Human Rights Charter,[154] womens’ rights activists have addressed structural obstacles to ending discrimination;[155] political activists have called for a referendum on the Islamic Republic, or shed light on Iranian leaders’ false claims about the representativity of the political system;[156] and ordinary Iranians have taken to the streets, protesting, and calling on clerics to let go of power.[157]

Rather than to engage with citizens on a constitution that was drafted in circumstances that seriously undermined its legitimacy – a constitution that a majority of Iran’s current citizens[158] never got the chance to approve or even opine on – the Islamic Republic’s leaders have, through the four decades since the Tabriz unrest, continued to arbitrarily shoot, prosecute, punish, and force into exile those who speak up or protest.

The new President of the Islamic Republic Ebrahim Raisi, a former prosecutor and chief justice, has been accused of crimes against humanity for his role in the secret killing of several thousands of political prisoners in the summer of 1988.[159] His then assistant, Hamid Nouri, is now being prosecuted in Sweden for his role in the killings.[160] More recently in his role of Chief Justice, Ebrahim Raisi oversaw the arbitrary arrest and summary prosecutions of thousands of protesters, as well as the arrest and imprisonment of those seeking justice for loved ones shot dead during the protests of 2017, 2018, and 2019.[161] As per the constitution and contrary to the assertions of Iran’s leaders,[162] the majority of citizens had no say in the process leading to his nomination and have no means to hold him accountable for his deeds.

Far from being representative of Iranian culture or from being "overwhelmingly approved by the people,"[163] the constitutional law was endorsed by neither the most prominent and respected members of the religious establishment nor a majority of the Iranian public. The Islamic Republic leaders owe their survival to violence and the ironclad monopoly on power granted to them by an undemocratic constitution drafted in dubious circumstances and in a context of electoral fraud and vigilante violence.

Iranians who seek to establish the rule of law in their country have had to reckon with the same concerns that compelled Ayatollah Shariatmadari to speak out forty years ago against the constitutional articles granting ultimate and unchecked power to unelected religious leaders. Any step to meaningful reform will also come up against Article 177, which stipulates as “unalterable” any constitutional article related to the Islamic character of the political system, objectives of the Islamic Republic, or guardianship of the theologian. A key step in bringing about democratic changes in Iran will be to challenge the legitimacy of a constitution that denies Iranians their human rights – in particular, the possibility of reforming laws that bar them from having a say in their own destiny.

[1]Iranian officials claimed that 75.2% of eligible voters participated in the referendum and 99.5% approved the draft constitution in early December 1979 (Donya-ye Eqtesad, “The Referendum on the Constitution in 1979,” December 3, 2018, https://www.donya-e-eqtesad.com/fa/tiny/news-3470386). “What I want to discuss with our dear nation today is about our magnanimous Imams’ most important innovation… : the innovation of establishing the Islamic Republic… which is synonymous with religious democracy, which was formalized under the title of the Islamic Republic and which turned into a system originating from the thoughts and willpower of the Iranian nation and from the leadership of our magnanimous Imam” (Khamenei.ir, “Imam Khomeini guided the Iranian nation to determine their own fate,” June 4, 2021, https://english.khamenei.ir/news/8524; “Statement on the 12th anniversary of the passing of Imam Khomeini,” June 4, 2001, https://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=3068; “Statement at the great gathering of the people of Kermanshah,” October 12, 2011, https://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=17510).

[2] Several publications point to widespread outcry over the removal of democratic process from the constitution in favor of velayat-e faqih. See the open letter from the Iranian Jurists' Association stressing that “no single individual or group can expropriate [national sovereignty] for its own purposes” (June 21, 1979, https://www.iranrights.org/library/document/1551); a communiqué from the Iranian Bar Association (February 27, 1979, https://www.iranrights.org/library/document/251/in-defense-of-rights-and-liberty); and an open letter from the National Democratic Front dated June 3, 1979: “[if by "government" and "constitution" you mean] the creation of a theocracy in which all action depends on clerics and the Quran, why talk about a constitution at all?” (https://www.iranrights.org/fa/library/document/254/the-national-democratic-fronts-open-letter-to-ayatollah-khomeini). Le Monde, December 4, 1979; Ettelaat daily, December 5, 1979. According to the Tabriz Governor, some ballot boxes were returned without votes, and no one accepted the responsibility of overseeing voting in at least six neighborhoods with polling places; meanwhile, multiple provinces witnessed tensions and clashes (The New York Times, December 3, 1979).

[3]Mohsen Kadivar, December 16, 2013, “Restoring the Dignity of Ayatollah Shariatmadari” (https://kadivar.com/10142/);Mashallah Razmi, 2000, “Azerbaijan and the movement of Shariatmadari’s Supporters in 1358,” Stockholm Tribune, Volume 1, pp. 23-25.

[4] ABC interviews with Hassan Shariatmadari, January 12, 2022, and Mashallah Razmi, February 3, 2022;