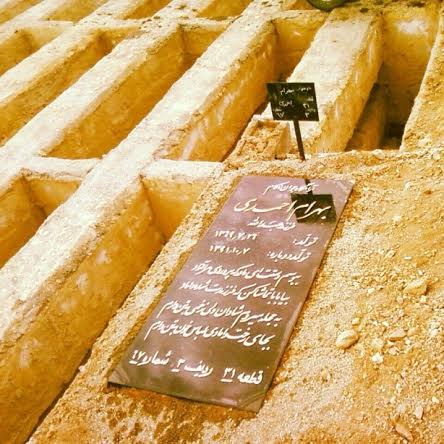

Two years ago, in late December 2012, six young men, Kurdish religious activists, were hanged in Raja’i Shahr Prison, in Karaj (Iran). The execution of Bahram Ahmadi, Asqar and Behnam Rahimi, Hushiyar Mohammadi, Keyvan Zand Karimi, and Mohammad Zaher Bahmani, was shrouded in secrecy, as was the judicial process that stripped them of their rights to due process and fair trial. The six young men were not the only victims of this unfair trial. They were tried along with four other young fellow activists, Hamed Ahmadi, Jamshid and Jahangir Dehqani, and Kamal Mola’i who are at imminent risk of execution.

Sunni Muslims are estimated to constitute about 10% of Iran’s total population. According to Article 12 of the Islamic Republic’s constitution, they can practice their faith freely.[1] In practice, however, the Shi’a rulers of Iran have subjected Sunnis to discrimination and have denied them political, civil, economic, social, and cultural rights, through restrictions in access to government positions, employment, education, and places of worship. Sunnis live in a majority in the most impoverished provinces of Iran, such as Kurdistan, Turkmen Sahra, and Sistan & Baluchestan, and the uneven distribution of resources remains one of their main grievances, vis-a-vis the central government.

Many of the grievances of Kurdish activists are not new. Over the years, multiple Kurdish and non-Kurdish sources have pointed to existing problems and have called on Iranian authorities to change laws and practices that isolate and antagonize ethnic and religious minorities. Comprehensive reports and multiple recommendations by the United Nations special rapporteurs on Adequate Housing, Violence Against Women, Religious Freedom, and groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, among others, seem to have fallen on deaf ears. As for local activists, expressions of grievances and organized dissent have landed them in prison, if not in cemeteries.

In the late 2000s, pressure on Sunni Muslims increased throughout Iran. Restrictions on places of worship that may be aimed at encouraging Sunnis to pray in mosques controlled by Shi’a clerics, have intensified, in particular on religious holidays, exacerbating already deep-rooted resentments. Sunni clerics have been detained, imprisoned, exiled, and even executed (in Baluchestan, in particular) for the vaguely worded offense of “waging war against God.”

In April 2009, for example, Shahram Ahmadi was shot in the back and arrested for his religious activism in Sanandaj. He was sentenced to death after 33 months of interrogation and solitary confinement. In January 2010, 19 Sunni clerics were reportedly arrested for spreading Sunni teachings in Kurdistan, Kermanshah, Baluchestan, West Azerbaijan, Ahvaz (Khuzestan), Tavalesh (Gilan) and Khorassan provinces. Scores of Sunni activists are in prison today across Iran. In his August 27, 2014, report, the UN Special Rapporteur on Iran wrote that at least 150 Sunni Muslims are currently “detained for reportedly organizing religious meetings and activities or after trials that allegedly often failed to meet international standards.”

That Kurds feel compelled to act in the face of decades of deprivation and discrimination in their region and, more recently, insults to their sanctity by local Shi’a clerics, is not a surprise. But one could legitimately wonder how, based on a tried and failed approach, the Islamic Republic authorities continue to imprison and kill activists, after summary trials, in the hope of eliminating discontent.

Very little is known of the case of the young men executed two years ago and their fellow activists currently on death row. Most of them were in their late teens or early twenties when they were arrested. Iranian officials have not made any statement on the judgment, nor have they provided the defendants with a copy of their sentence. According to the prisoners, the main charge against them is “propaganda against the regime through participating in religious and ideological classes and distributing cd’s and books.” They also report that the court relied on defendants’ confessions acknowledging “links to Salafi groups, with the aim of overthrowing the regime” to convict them of “waging war on God.”

In their own defense, which, they say, the court did not see fit to hear, these prisoners stress that their confessions were extracted from them after months of torture and solitary confinement, and promises of leniency. They vehemently deny any armed action or affiliation with Salafi groups and note that some of them had initially been charged with the assassination of local clerics, which had taken place weeks after their arrest. In their letters and statements from prison, they stress that their religious activities were peaceful and point to discrimination against Sunni Kurds that affect their livelihood and to the insulting and disparaging statements of local Shi’a clerics against their beliefs as the root cause of their activism.

These prisoners believe that their persecution is aimed at halting their efforts to promote their own interpretation of Islam and to raise awareness among their fellow Sunnis about the unjust treatment of Sunnis and the misuse of religion by the ruling elite. Before his trial, Bahram Ahmadi had reported that his interrogators had clearly told him that he will be executed, because by promoting his religious views and criticizing the authorities’ interpretation of religion, he had engaged in a war on God.

Human rights organizations have expressed serious concerns about “the situation of 33 Sunni Kurds, most of whom are held in Raja’i Shahr Prison in Karaj and are, in the case of some of them, at imminent risk of execution. They have pointed to their “grossly unfair trials, during which basic safeguards, such as the right to defense, were disregarded, in contravention of international fair trial standards.” In open letters to authorities, Iran’s Sunni religious figures have also pleaded in favor of the young activists.

Incommunicado detention, up to two years in some cases; torture to coerce self-incriminating confessions; lack of access to a defense attorney of their choosing, and denial of their rights to defense; all typify a prosecution that is weak on evidence. Other decisions, such as that of referring these men to Judge Mohammad Moqiseh, head of Branch 28 of Tehran’s revolutionary court and notorious for his politically motivated and harsh sentences, rather than in Kurdistan, where the alleged crimes took place; refusing access to their file to them or to their assigned lawyer, who saw the defendants for the first time half an hour before their trial; or trying them in a ten-minute session, while shackled and blindfolded, are not indicative of a strong case either.

Iranian authorities, and judicial officials in particular, should hear the plea of the Sunni prisonersand their families who demand the annulment of their death sentence (based on Article 10 of the Penal Code) and a retrial. They should recognize that by admitting coerced confessions as evidence and sentencing defendants to death following a 10-minute long session, Tehran’s revolutionary court has failed to meet the requirements of a fair trial and Iran’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The Judiciary should either ensure that these prisoners are retried in a transparent and public judicial process where defendants are provided the means to prepare a proper defense, or release them.

Abdorrahman Boroumand Boundation

31 December 2014

_________________________________

[1] "The official religion of Iran is Islam and the doctrine, that of the Twelver Ja'fari school [in Usul al-Din and fiqh], and this principle will remain eternally immutable. Other Islamic schools, including the Hanafi, Shafi'i, Maliki, Hanbali, and Zaydi, are to be accorded full respect, and their followers are free to act in accordance with their own jurisprudence in performing their religious rites. These schools enjoy official status in matters pertaining to religious education, affairs of personal status (marriage, divorce, inheritance, and wills) and related litigation in courts of law. In regions of the country where Muslims following any one of these schools of fiqh constitute the majority, local regulations, within the bounds of the jurisdiction of local councils, are to be in accordance with the respective school of fiqh, without infringing upon the rights of the followers of other schools."