An Indictment Against My Own Conscience

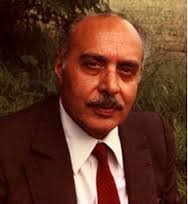

On the Occasion of the 17th Anniversary of the Assassination of Abdorrahman Boroumand

In an article published in 1945, Hannah Arendt, a twentieth-century Jewish intellectual of German descent, wrote that she has had many encounters with German people who would tell her they were ashamed of being German, to which she would respond: “that I am ashamed of being human[1]

Perhaps it is our common human essence to feel responsible for the tyranny that befalls human beings. From the famous lines of the thirteenth-century Persian Poet, Sa’di (1195-1226) [2] to the French penal code that considers it a crime not to help an individual in danger, to the creation of organizations such as the Red Cross, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch or Doctors without Borders, one finds responses by human beings to their sense of guilt over and responsibility for calamities that they have neither ordered nor carried out.

In a century of countless crimes against humanity, many victims, politicians, lawyers, and intellectuals have reflected on this matter and put their thoughts and experiences into words. We have, thus, a rich literature regarding the importance of memory to draw on in our perilous path to democracy.

Twenty-nine years ago, a regime based on the negation of human rights was established in Iran. Since then the Iranian nation has witnessed a constant violation of rights and infliction of violence unprecedented in the contemporary history of the country. The question is one of what to do to end this violence and support the rights of individuals? We could continue to point the finger at the individuals who have ordered, carried out, and assisted in murders and all forms of summary executions. We could continue to demand a just trial to investigate the criminal charges of the officials and authorities of the Islamic Republic of Iran and punish them if their charges are confirmed. Of course, this is our ultimate goal, but for the time being, the accused are in power and the world is little concerned with bringing justice to the victims of summary executions in Iran.

So we must find another way. Maybe there is something we can do to bring the day of justice closer. Maybe the best way to the pave the ground for the implementation of justice is to refer to our own conscience and reflect on our responsibility as Iranian citizens. Maybe then we can see the dimensions of this responsibility reflected in the mirror of memory, we can take our suffering conscience to court and ask ourselves why and how we managed to make such a mistake. For we did make a mistake on the day when we rushed by the millions to the ballot boxes and decided, with so much exuberance, such a tragic fate for ourselves, our children and our country.

The bloodied face of General Nasiri that appeared on television screens moments after the success of the Revolution should have destroyed any illusions about the nature of the new rulers, for whom justice was synonymous with revenge. I remember so well that cursed morning on one of the last days of winter at the entrance to the Isfahan Bazaar, standing in shock in a crowd of people from various walks of life who were staring in deadly silence at the images of the bullet-pierced bodies of the Royal Army officers posted on the wall. It felt as if the images carried a message from the new rulers to the people of Iran. A clear message of despotism, autocracy, revenge, and violence. The nature of the Islamic Republic, otherwise as yet unclear, could be seen clearly in these images. And it appeared as though people, in their silence, bore witness to the emergence of a violent despotism. And thus began the nightmare of executions. I found myself regretful and ashamed in the face of those images of the bodies of yesterday’s rulers who had now joined the ranks of the victims. Regretful, because my heart had been with the Revolution; ashamed, because I had not sensed the dimensions of danger. On that day, my conscience lost its innocence forever.

With the executions came the suppression of all forms of dissidence. Those who, like Parviz Osia, had courageously written in opposition to the execution of innocent individuals (such as Captain Monir Taheri who was falsely accused of having had a hand in the Cinema Rex fire in Abadan) were immediately jailed. The slogan “Islamic Republic, not a word more, not a word less” ended the public debate about the future government of the country, and the courageous men of yesterday simply bowed in obedience. Millions of Iranians said “yes” to the Islamic Republic, ignoring firing squads and Revolutionary Tribunals and, consequently, legitimizing as democratic the official’s unforgivable crimes. It should come as no surprise, then, that the conscience of the Iranian society as a whole be questioned in the court of history.

As I reach back into my memory, I come across the angry glance of a desperate young woman who fought single-handedly for several days to save her uncle from execution and who was finally called to the prison to receive his body, the body of Gholamreza Nikpey, the former mayor of Tehran, which she buried all by herself and with no ceremony. Not even her husband dared to accompany her. The sheer wrath and turmoil in that look shook me to the core and reminded me of the destructive power of rage and upheaval resulting from tyranny and injustice.

The look on the face of the young woman brings to mind the words of another woman who, upon hearing of Nikpey’s execution, said: “They did well by killing him.” Not two years had passed after that unfortunate comment when her face appeared on French television. She was being interviewed as a prisoner in Evin Prison. She had clearly endured severe torture and no teeth had remained in her mouth. She and a thousand other political opponents had been caught in the grip of a raging force that they themselves had helped establish and strengthen by shouting “Must Be Executed!” when it came to others.

I was still in Iran when women’s demonstrations against mandatory veiling shook the foundations of the Islamic regime and the Hezbollah attacks, with knives, rocks, and knuckle-dusters, on those peaceful demonstrators taught people a lesson in their new rulers’ definition of civil liberties. On May 1, 1979, I packed my belongings and left Iran. I knew that I would not see my homeland for a long time. I returned to my studies which had been interrupted for a short while and took refuge in my books with an aching heart. As I searched for reasons for this collective mistake in the peace and quiet of a Paris library, floggings and executions were becoming increasingly frequent in Iran. Along with the mass murder of political activists, they murdered many helpless people under the pretext of drug addiction and smuggling. In Kurdistan, the dimensions of massacre were unimaginable.

I leaf through the Kayhan newspaper of August 29, 1979, for instance: The first page announces the execution of fourteen prisoners in Tabriz. The second page has the names of two Kurdish citizens executed in Zanjan. On the third page, there is the news of the execution of twenty people from Saqez, nine of whom were army officials. It suffices to look at the details provided about the execution of the Saqez residents: Sheikh Sadeq Khalkhali, the first Religious Judge of the Islamic Revolutionary Tribunals, arrived in Saqez on the evening of August 27, 1979. At seven the next morning, the twenty victims faced the firing squads. Even if the Religious Judge did indeed hold trials from the moment he arrived in town until seven in the morning, not more than a few minutes could have been spent on each case. The army officers were executed for abandoning their post, which most probably means that they refused to shoot the people during mass demonstrations. On page eleven of the same newspaper, there is the news of the execution of Ali Mirshekari, another dissident whose crime was carrying leaflets of different political groups, next to the report of the execution of a man and woman for alleged adultery in Bushehr.

A year later, in the summer of 1980, the best of the army and several civilian men and women were executed for participation in plotting a coup d’etat called Nojeh. Their crime consisted in their wish for a social democratic government complete with all political freedoms. They lost their lives in their struggle to achieve that which is the natural right of every human being, because the Islamic Republic had left them with no other option. The memory of the Nojeh Uprising evokes the story of Shahriar Noor, the eighteen-year-old son of Amir Hushang, who was arrested for being the son and who was sentenced to death in place of the father. His murderers postponed carrying out the sentence for two days in the hope that he would reveal his father’s hiding place under torture in order to save his own life. They executed Shahriar Noor on August 6, 1980 and returned his shattered body to his mother. Eleven years later on the same day, Shapur Bakhtiar and his faithful companion, Sorush Katibeh, were stabbed to death in Paris by two members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards and an infiltrator.

I wander on, dragging my guilty conscience through the twists and turns of memory, and I encounter the smiling face of Manuchehr Mas’udi, an attorney with the Ministry of Justice and an old friend of my father’s who joined the supporters of IRI first President, Abolhasan Banisadr, during the Revolution and spent all of his time taking care of people’s complaints. Maybe it was he who on one of the pages of “Enqelab Eslami” [Islamic Revolution] newspaper revealed the corruption and torture common in the Islamic Revolutionary Public Prosecutor’s Office in Saveh. Perhaps we have to be thankful to him for the document we now have regarding the execution of Ms. Razieh Fuladi. Razieh Fuladi was found guilty of “illicit relationship with a man” after one session of trial at the Revolutionary Tribunal of Saveh and was executed early morning on Thursday, August 30, 1979. On February 20th the next year, her husband, Mr. Ne’mat Barak Nil, wrote in a letter to Khomeini: “My wife was innocent. They took her to the [Revolutionary] Committee of Saveh on August 28th and flogged her so much that she had no choice but to lie and say that she had committed adultery; they then executed her three days later. This is while as her husband I had no complaints about her and everyone in the neighborhood knows that my wife had been pure and innocent. Now I have been left alone with four small children who don’t have a mother to look after them.”

As I review the names of these victims, I ask myself that if the children of Abdorrahman Boroumand, Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar, Sa’idi Sirjani, Pouyandeh, and Mokhtari can tell the story of the cruelty endured by their loved ones and have the world hear their pleas for justice, who is going to tell the story of that lonely and illiterate woman whose children have most probably never heard of Amnesty International or the Human Rights Council of the United Nations and who do not have the voice or the vocabulary to contact anyone and seek justice? How many times have we heard of a woman stoned for adultery? How many of them have been forced to confess under torture? Which of us has pursued her case and recorded her sorrowful tale in history?

The news of Manuchehr Mas’udi’s execution came to us from a friend in Paris after Banisadr had fled the country, following his impeachment by the clergy dominated Parliament. The criminals never forgave him for his attempts to seek justice. A while later, his young wife left Iran with their two children and took asylum in France. In a visit, she talked about how her children’s teacher had badmouthed and humiliated them in class the day after their father’s execution and how it had become unbearable for the children to stay in that atmosphere any longer. Around the same time as Manuchehr Mas’udi’s execution, the rule of terror in Iran was intensified. I remember well that sense of desperation and helplessness as the tragedy unfolded. We were dumfounded and paralyzed by the eruption of beastliness and blood and violence in our country. Shahrnush Parsipur’s memoir has nested in a corner of my mind: “In prison, we would lay in bed every night with a disturbed soul and a clamped heart, counting the shots from the firing squads; and some nights, the numbers reached two hundred.” Only on one night, at one prison, in one city in Iran!

From among thousands of young men and women who faced firing squads for no crime, my memory rests on the smile of a seventeen-year-old girl by the name of Mona Mahmudnizhad. Her laughing eyes light up her beautiful face and the locks of her hair intensify that light. She was detained for a few months. They wanted her to denounce her Baha’i faith and she refused. They hanged her along with nine other Baha’i women on Saturday morning, June 28, 1984.

And every day, new bodies added their weight to our conscience. We went through life with our heads down, trying to lighten our burden by publishing a statement or putting together a partial list of victims’ names. And the list continued to grow and soon the names of not only people we knew but our own loved ones were added to the list. One day we heard that Khosrow Qash'qa'ii was hanged. A courageous man, free-spirited and patriotic, a loyal friend. Burning in guilt and grief, I asked myself, where are we, where are we all, when the victim walks with the executioner to meet death? Why does the world suddenly turn into a vast desert the only inhabitants of which are the victim and the executioner? Isn’t the number of those who oppose these crimes larger than the number of those who endorse them? Twenty-nine years have passed since the curse of the Islamic Republic began and I am still haunted by this question.

With time, I got used to living with shame. I found myself back in the library, searching to comprehend the ideological foundations of terror. I started studying the history of the French Revolution. Hearing news of murders and executions in Iran became an everyday occurrence. Until Thursday, April 18, 1991. It was around noon when I closed the last of the ninety-two volumes of the proceedings of three Legislative Assemblies during the French Revolution and sighed with relief. The National Convention reached a decision to have Robespierre arrested; one of the terrorists himself became the last victim of the Reign of Terror. And with this verdict, the almost seven years of research about the ideological and philosophical foundations of terror had come to an end. After years of research, finally the time had come to write. I felt as if a weight had been lifted from my shoulders. The city was lay spread out beneath the low clouds through which the sun peeked every once in a while, and the spring breeze caressed the face of Paris.

The phone rang. The shaking voice of my young brother carried the news of an attack on our father. I rushed home. My father was still there on the ground. The police didn’t allow me to hold him in my arms one last time. The doctor at the scene told me that he had died. And with his death our lives changed forever. That ever-present shame that had become part of my existence turned into a raging storm that shattered my home and body and spirit. It was then that I asked myself, what right do I have to live? With this personal tragedy, I went through the tragedies that had befallen our country during the years that I had buried myself in my studies.

Where was I and what was I doing in those cursed months of the Summer of ’88 when inquisitorial three-member committees were busy murdering the best of our country’s youth? Those who resisted force and stood by their ideas taught their murderers that the human conscience will not be captive and that no power is strong enough to deny the freedom that is inherent in the human spirit. They won against their enemies with their death. It was such a victory that the executioners had to deny not only the murders but the existence of those several thousand citizens. Where was I when the resistance of those prisoners took on an epic quality? What was I doing?

I had relegated he news of the murder of Dr. Elahi, who was killed in Paris a few months before my father, to a corner of my mind. I knew of the murder of Qasemlu in Vienna and all I had done was to feel sorry! I thought about the assassination in Austria of Hamid-Reza Chitgar. For months, his wife and sister searched for him in agony until his body was found and his relatives in France were notified. I hadn’t even received news of this incident, let alone put it together with the other murders of Iranians abroad to notice the regime’s general policy of eliminating its opponents.

I wish this sorrowful tale had ended with the murder of my father. Alas, extrajudicial murders and summary executions continued. Remember Mr. Feyzollah Mekhoubad? He was one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Iran. He was arrested for “espionage for Israel.” They had used his phone calls to his relatives in Israel and America as evidence of guilt against him. He was executed in the winter of 1993. His body bore the marks of torture and his eyes had been poked out. Or Mr. Haik Hovsepian-Mehr, our Christian compatriot who refused to sign a letter that claimed that the Islamic Republic respected freedom of religion, and lost his life as a result? And the murders went on. Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar, old friends of my father, soon shared his fate. So were other different-minded individuals whose names I shall never forget. Those, like Zalzadeh, who were killed inside Iran as well as those, like Sharafkandi and Dehkordi and Farokhzad, who were killed abroad. And Zahra Kazemi, and Shovaneh Qaderi, and Akbr Mohammadi, and Valiollah Feiz-Mahdavi. Or those who were arbitrarily killed by armed forces without any legal procedures, like Ali Ahmadipur, Mas’ud Khodabandelu, Seyyed Mostafa, Ebrahim Lotfollahi, Zahra Baniameri, and others. And the list goes on….

By looking at the endless list of victims, I reflect upon the beginning of Khomeini’s sedition, and my mind starts wrestling with the how and why of it. Twenty-nine years ago, at the threshold of the fall of dictatorship, the Iranian nation faced a quandary. It saw in Shapur Bakhtiar’s plan the vista of an unknown destiny that was the necessary ground for the foundations of liberty. Liberty whose other name is responsibility and whose being is mixed with anxiety. Liberty bids farewell to the responsibility-free comfort of vegetative being. Liberty that mobilizes the mind, the senses, and the will of the individual at every moment of life and never allows the conscience to rest. Liberty that, despite its heavy cost, is humanity’s only reconciliation with itself. Instead, an Imam appeared from moon[3] and delivered to the Iranian nation the promise of paradise at the expense of their freedom. At that moment, from fear of freedom, the Iranian nation took refuge in a false paradise and left its destiny in the hands of a guardian. Today, after twenty-nine years, faction after faction and group after group of Iranian people understand their horrifying mistake and realize that not only did they not find the comfort of the promised paradise, they also lost their dignity in this gamble and are wandering in an exasperating purgatory with no clear future.

In the history of the world, however, we are not the only nation that has erred. What has followed our error is an ongoing, relentless struggle by the Iranian people, and the fact that we remember, and remember with sorrow, is a testimony to the truth of this struggle. It is struggles of this sort that keep the torch of hope burning bright, call on vigilant consciences, and drive the search for a solution.

The pain and sense of guilt that disturbs the souls of people under despotic regimes results from their helplessness against the tyranny they witness. We can answer the call of our consciences by testifying against the tyranny that we have not been able to prevent. To ensure the validity of her testimony, the Kurdish nurse Shahin Bavafa asked the French journalists to make sure to put her name to her testimony about the suffering endured in Sanandaj by residents and hospitalized patients. She was executed for this testimony. Amir Entezam was still in prison when in a radio interview he testified about what he had witnessed in prison, and they renewed his detention. In one of his breaks from custody, Ahmad Batebi reached a UN representative to testify about the disappearance of his friends, and he paid the price with strikes of the whip. Today, human rights activists risk their lives to systematically send out the news of human rights violations and, thus, uncover the face of injustice in Iran. Babak Dadbakhsh was exiled to one of the most notorious prisons in Iran because of his report about prison conditions and had to sew his mouth shut and go on hunger strike to protest the extreme mistreatment that he endured there. This kind of courageous behavior stems from an urge, the urge to testify.

Heroes are ornaments to history, but history is made of the lives and actions of ordinary people. We do not need to be heroes; it is enough to be inspired by heroes. We have a right to be afraid of violence; we do not want to sacrifice our lives and that is understandable, because democracy is founded on the right to life and happiness. Thus, we have to choose our path wisely.

Isn’t it true that liberty and responsibility are the two sides of the same coin? Maybe if each of us accepts the responsibility to his or her own conscience, together we can restore our own dignity and the dignity of all the victims and thus gain back our freedom. To analyze and understand this responsibility, we must first know the extent of the calamity we face. We must record the cruelty and injustice of the Islamic Republic in all its spheres. Each of us has buried the memory of an injustice in the corner of our minds. These memories have to be brought to life free of lies and exaggerations and offered as a gift to the historical memory of our country. The day when the complete collection of these tragedies is restored in the collective memory of the Iranian nation and other people of the world through the efforts of thousands of Iranians is the day that those who ordered, carried out, and assisted these crimes will be too ashamed and humiliated to dare repeat their actions, even before any trials regarding their crimes have taken place.

We have already seen how the spontaneous attendance of several thousand citizens at the funeral of Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar and the public expression of disgust with these murders was such a slap in the criminals’ face that even the ones who had ordered the crimes themselves had to condemn them officially. Witness C, Mesbahi (former IRI intelligence agent), risked his life and accepted the possibility of exile by revealing the identity of the ones who had ordered the assassination of opponents abroad and by doing so perhaps saved the lives of many other exiled opponents. This is because the criminals are afraid of the memory of/and witnesses to their crimes lest the image of their villainy wipes out the source of lies and illusions upon which feeds their utopia. Recording calamities and fighting against oblivion are options that are available to all citizens and do not require arms, funds, and logistics. They require love and wisdom, a strong will and a pen.

It would be unfair to let the wailing of the victims be buried under the silence of time, leaving the deceptive and contemptuous accounts of criminals as the only narratives left for history to judge.

There is another purpose to the preservation of a collective memory, one that concerns omid [hope in Persian] and the future. Acknowledging cruelty and injustice and restoring the dignity of the victims pave the ground for national reconciliation, for they comfort the souls of hundreds of thousands of survivors and guard against another outburst of violence, a potential that holds the seeds of the next tyranny.

[1] H. Arendt, "Organized Guilt and Universal Responsibility", in The Portable Hannah Arendt, Penguin Books, London, 2003, p. 154.

[2] Human beings are members of a whole,

In creation of one essence and soul.

If one member is afflicted with pain,

Other members uneasy will remain.

[3] Referring to claims by many of Khomeini’s supporters in the days leading to the Revolution that they had seen his face on the moon!